To identify the prevalence of non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies in a systematically randomized sample of symptomatic, non-presbyopic subjects from a tertiary hospital, using a broader range of diagnostics signs.

Subjects and methodsThe study was designed as hospital-based, cross-sectional, and analytical and was conducted from March 2022 to April 2023. Systematic random sampling was employed to select the subjects. Symptomatic subjects aged between 18 and 35 years with best-corrected visual acuity of 6/6 in each eye and no change in refractive error during the subjective refraction were included in the study.

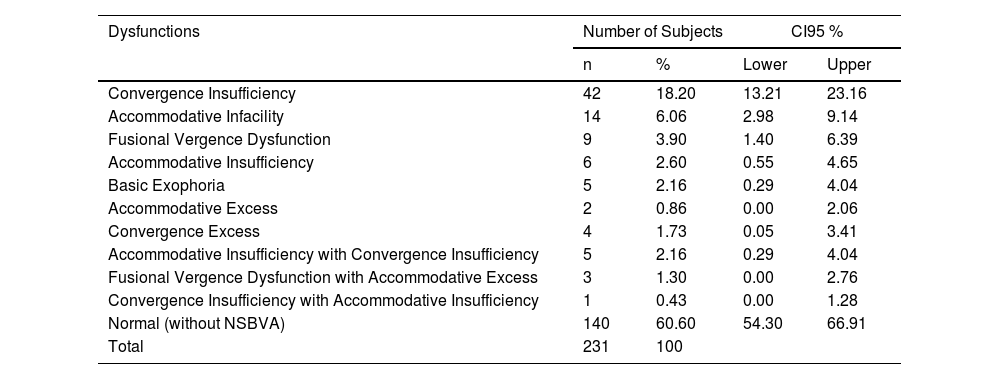

ResultsOut of the 231 subjects examined, 91 (39.39 %) were found to have non strabismic binocular vision anomalies. Of all the non strabismic binocular vision anomalies, 60 subjects (26 %) had binocular dysfunctions, 22 (9.5 %) had accommodative dysfunctions, and 9 (3.9 %) had both accommodative and binocular dysfunctions. The most common dysfunction was convergence insufficiency (18.2 %), followed by accommodative infacility (6.06 %) and fusional vergence dysfunction (3.9 %). The most prevalent symptom was headache (16.7 %), followed by visual fatigue (14.1 %).

ConclusionTwo-fifths of the symptomatic subjects have non strabismic binocular vision anomalies. It is essential to assess all accommodative and binocular parameters in order to arrive at a diagnosis of non strabismic binocular vision anomalies.

To maintain a clear vision when reading or doing near tasks, both accommodative and vergence systems must be adequate. Failure of these systems can cause accommodation and vergence dysfunctions.1 These dysfunctions might impair a child's academic growth or a person's ability to perform well at work.2 These dysfunctions are grouped together under the umbrella term “Non-Strabismic Binocular Vision Anomalies” (NSBVA).3 Some researchers have observed that people who spend long hours on near activities, such as using a computer or reading, often report experiencing visual related symptoms,4–7 although recent research has reported that the main cause of symptoms is visual dysfunction, not the number of hours of electronic device use.8

Occurrence of NSBVA in hospital-based populations is relatively common. However, there is still some variation in the prevalence values in the clinical population presented by different authors.1,3,9–27 Currently, there is only one study with prevalence data on NSBVA in Nepal, although the main objective of the research was not to show prevalence data, and the sample used was somewhat small.28

It would be highly beneficial to conduct a study on the prevalence of NSBVA in a clinical population presenting with visual symptoms associated with visual dysfunctions, utilizing diagnostic criteria established in the scientific literature. Such a study could contribute to future epidemiological research and enhance knowledge regarding the management of NSBVA in Nepal.

Under this scenario, the aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies in a systematically randomized sample of symptomatic, non-presbyopic subjects from a tertiary hospital, using a broader range of diagnostics signs. The secondary objective was to explore the range of symptoms and analyze the distribution of age, gender and refractive errors among subjects with non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies.

Subjects and methodsThe study was designed as hospital-based, cross-sectional, and analytical and was conducted at the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology, Kathmandu. This site was chosen for its accessibility and the presence of relevant units. Systematic random sampling was employed in selecting the subjects, considering symptomatic patients who reported symptoms in the anamnesis. Over the course of one year, from March 2022 to April 2023, 231 symptomatic subjects aged between 18 and 35 years were assessed who visited the comprehensive and/or orthoptic department and met the inclusion criteria. Symptomatic subjects aged between 18 and 35 years with best-corrected visual acuity of 6/6 in each eye andchange in refractive error during the subjective refraction were accepted for participation. The upper age limit of 35 years was established to exclude pre-presbyopic and presbyopic subjects from the study (considering presbyopia when the patient needed addition), as their inclusion could bias the diagnosis of a NSBVA.29 Exclusion criteria encompassed various ocular and systemic pathologies, ocular surgeries, taking medication, neurological disorders, wearing contact lenses, anisometropia (more than 2.00 diopters), strabismus, or amblyopia.

This research was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Committee of Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology (Reference number 10/2022), Kathmandu, and adhere to the principle of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolling them in the study. Participant’s dignity and autonomy were preserved.

Initial history and complete ophthalmic evaluation including refraction (dry and cycloplegic), anterior and posterior segment examination was carried out in comprehensive department followed by complete binocular vision assessment in the orthoptics department. Binocular vision examination along with case history was carried out in the orthoptic department which included the following tests and procedures:

- 1.

A case history, with special emphasis on symptomatology. Data was collected based on symptoms reported by the subjects. Instead of a questionnaire, we used symptom categories from García-Muñoz et al.2 Scoping review, which detailed symptoms linked to NSBVA. Patients were presented with a list of 34 symptom categories and asked if they experienced any vision-related symptoms.

- 2.

Accommodative and binocular tests: The ocular deviation was assessed using a prism bar cover test at both near and distance. Step positive and negative fusional vergence (PFV and NFV) was measured with a horizontal prism bar at near and distance, with NFV measured before PFV. The Near Point of Convergence (NPC) was measured using a Royal Air Force (RAF) rule in primary gaze. The amplitude of accommodation was measured monocularly and binocularly with the RAF rule. Positive and negative relative accommodation (PRA and NRA) were measured using a phoropter (NRA was measured before PRA). The lag of accommodation was assessed by dynamic retinoscopy with the Monocular Estimated Method (MEM). Monocular and binocular accommodative facility was evaluated using an accommodative flipper ±2.00 diopters (D). The AC/A (Accommodative Convergence/Accommodation) ratio was measured using the gradient method.

NSBVA were diagnosed using the criteria established by Lara et al.19 For a diagnosis of dysfunctions, a subject needed to exhibit the fundamental signs along with at least two additional complementary signs specific to the dysfunction. Those who did not meet these criteria were classified as “normal”.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 20.0). Mean and standard deviation were used to describe the central tendency and dispersion of the study parameters respectively. All of the study parameters showed a normal distribution during the normality test using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p > 0.05). A comparison of values between the subjects was carried out using the unpaired t-test. The results were considered significant at p-value < 0.05 at a 5 % level of significance.

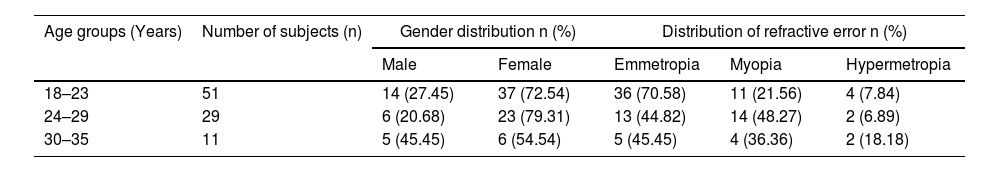

ResultsThe study included 231 subjects (149 female), with an average age (± Standard Deviation, SD) of 23.41 ± 4.92 years (from 18 to 35 years old). The mean (± SD) spherical equivalent of refractive error was −0.238 ± 0.75 D, with values ranging from +2.00 D to −4.00 D Emmetropia (56.7 %) was the most prevalent refractive error, followed by myopia at 35.5 percent and hyperopia at 7.8 percent subjects.

Out of the 231 subjects examined, 91 subjects (39.39 %) were found to have a NSBVA. This included 66 females, 54 emmetropes, and 29 myopes. The age, gender, and refractive error distributions for these dysfunctions are shown in Table 1. Of all the NSBVA subjects, 60 (26.00 %) had binocular dysfunctions, 22 (9.50 %) had accommodative dysfunctions, and 9 (3.90 %) had both accommodative and binocular dysfunctions. The most common dysfunction was convergence insufficiency (18.20 %), followed by accommodative infacility (6.06 %) and fusional vergence dysfunction (3.90 %). Among 140 subjects who did not have NSBVA, 66 % had at least one affected accommodative or binocular parameter. Table 2 shows the prevalence of NSBVA.

Age, gender, and refractive distribution among NSBVA subjects.

Prevalence of Non Strabismic Binocular Vision Anomalies.

NSBA: Non Strabismic Binocular Vision Anomalies.

CI 95 %: Coefficient Interval at 95 %.

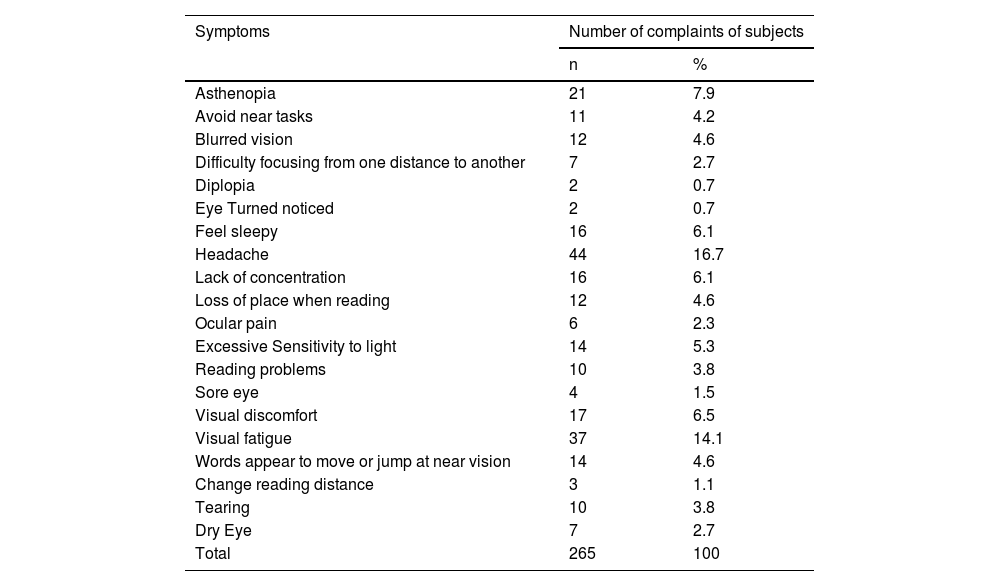

Twenty different categories of visual symptoms were reported by the 231 subjects. All subjects reported one or more visual symptoms. The most prevalent symptom was headache (16.7 %), followed by visual fatigue (14.1 %). Table 3 shows these different categories of visual symptoms, along with the number of complaints reported by the subjects.

Symptoms categories encountered in all subjects of the Sample.

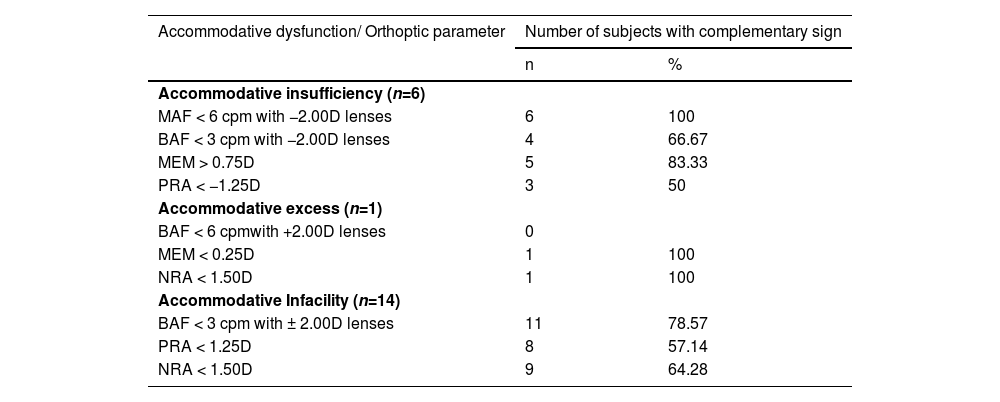

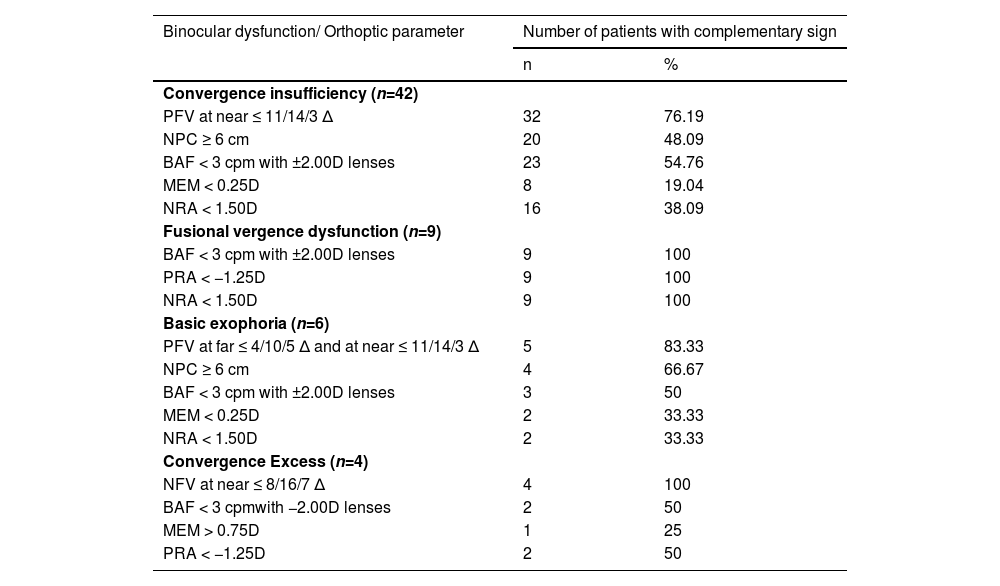

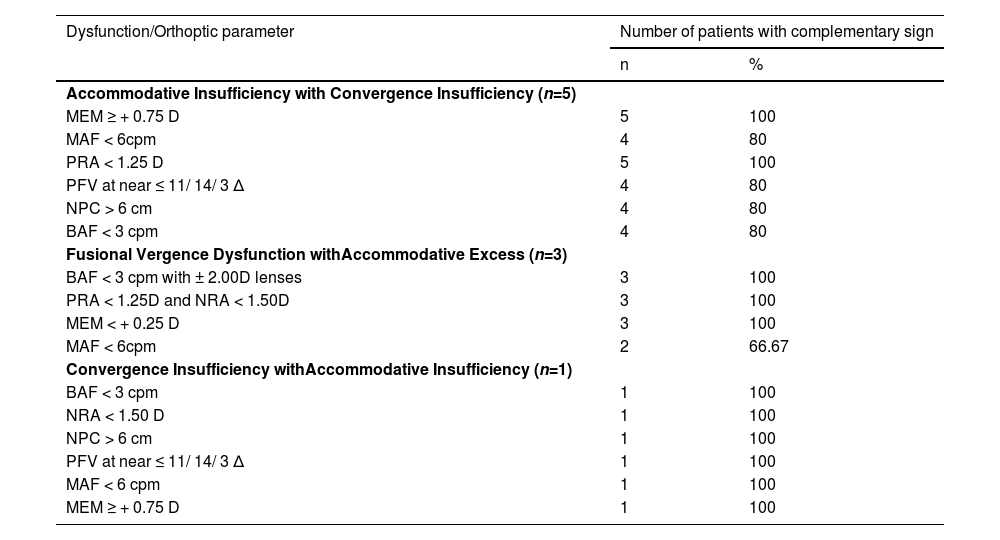

Tables 4, 5, and 6 show the number of subjects with each complementary sign of NSBVA. The most affected complementary clinical signs for accommodative infacility, convergence insufficiency, basic exophoria, and convergence excess were Binocular Accommodative Facility (BAF), Positive Fusional Vergence (PFV) at near, PFV at far and near, and Negative Fusional Vergence (NFV) at near, respectively.

Number of subjects with complementary sign among accommodative dysfunctions.

MAF: Monocular Accommodative Facility, BAF: Binocular Accommodative Facility, MEM: Monocular Estimated Method, PRA: Positive Relative Accommodation, NRA: Negative Relative Accommodation.

Number of subjects with complementary sign among binocular dysfunctions.

PFV: Positive Fusional Vergence, NFV: Negative Fusional Vegence, NPC: Near Point convergence, MAF: Monocular Accommodative Facility, BAF: Binocular Accommodative Facility, MEM: Monocular Estimated Method, PRA: Positive Relative Accommodation, NRA: Negative Relative Accommodation.

Number of subjects with complementary signs among accommodative and binocular dysfunctions.

PFV: Positive Fusional Vergence, NFV: Negative Fusional Vegence, NPC: Near Point convergence, MAF: Monocular Accommodative Facility, BAF: Binocular Accommodative Facility, MEM: Monocular Estimated Method, PRA: Positive Relative Accommodation, NRA: Negative Relative Accommodation.

There were significant differences in BAF (p < 0.005), MAF (p = 0.02), PFV break and recovery for near (p < 0.005), NRA (p < 0.005), and PRA (p < 0.005) between subjects with and without NSBVA in this studied populations. However, for all other clinical findings, the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

DiscussionThis study was conducted to determine the prevalence of NSBVA in symptomatic subjects from tertiary eye hospital. Currently, only one study in Nepal has reported prevalence data on NSBVA.28 However, its primary objective was not to determine prevalence, and it was based on a relatively small sample. Therefore, this study is the first to specifically assess the prevalence of NSBVA in a clinical population. According to the results of this study, the prevalence of NSBVA in the hospital-based population is important from a clinical point of view. Among 231 subjects examined, 92 (39.82 %) presented some kind of NSBVA. The most common NSBVA was convergence insufficiency (18.2 %).

The prevalence of NSBVA observed in this hospital-based population study is lower than that reported in other studies conducted in similar populations.12,22 Conversely, it is higher than the prevalence reported in studies involving clinical populations, where values ranged from 19.30 % to 32.00 %,19,21,23 and even greater than those found in the general population, where prevalence ranged from 13.15 % to 31.50 %. These differences may be attributed to the characteristics of individuals attending the hospital, where the likelihood of presenting a visual problem is higher compared to clinical or general populations. Additionally, variations in prevalence values may be influenced by study design, inclusion criteria—which tend to be more restrictive in clinical studies than in general population studies— or differences in diagnostic criteria.

To accurately diagnose NSBVAs, a complete battery of binocular vision tests was carried out as well as standard clinical diagnostic signs to measure binocular and accommodative parameters. In the scientific literature, there are numerous diagnostic criteria for these dysfunctions.30 NSBVA were diagnosed in this study using the criteria proposed by Lara et al.19 Different diagnostic criteria (in terms of the cut-off points of tests and number of criteria) used to classify anomalies, type of population studied,30 study design and sampling method may be the main factors causing variations in the prevalence of dysfunctions in the various studies.31 Some studies reference the classification proposed by Scheiman and Wick,9,11,12,27 while others adopt the classification by Lara et al.,19,21,23 as applied in the present study. As highlighted in the systematic review by Cacho-Martínez et al.,30 diagnostic accuracy studies indicate that evidence regarding accommodative conditions remains limited, with considerable variability in the diagnosis of binocular dysfunctions.

Similar to this study, the prevalence will be higher in the hospital based population than in the general population because hospital based populations are more likely to complain of visual problems than the general population.2,18,19,21 In this hospital based study, we evaluated the prevalence of NSBVA among symptomatic non presbyope age group. Hokoda studied the prevalence of general binocular dysfunction in asthenopia non-presbyopes in an urban clinical population and found that 21 percent of subjects had NSBVA.32 As diagnosis was made based on one or two clinical signs, it is difficult to compare their results to those obtained in our study. Similarly, Lara and colleagues found 59 (22.3 %) subjects with NSBVA among 265 consecutive symptomatic Spanish clinical populations of aged between 10 and 35 years.19 The diagnostic criteria used in this study were similar to our study but there is a much variation in the prevalence of NSBVA compare to our study, which may be related to the age of the subjects and inclusion of refractive dysfunction.

The study included individuals aged 18 to 35 years, with a higher proportion of females than males. Non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies were found to be more prevalent among females and those aged 18 to 23 years. This age group is often involved in prolonged near-visual tasks, such as studying and screen use, which may contribute to the higher prevalence of dysfunctions. Furthermore, females are generally less active outdoors compared to males, which could account for their larger number, both in the study and among those with binocular vision dysfunctions.

In addition, it was obatined that binocular dysfunctions were more prevalent than accommodative dysfunctions, as in previous research.18,19,21,22 In our study, 61 subjects (26.40 %) were diagnosed with a binocular dysfunction. This prevalence is more than that reported by Ovenseri-Ogbomo and Eguegu18 (12.7 %), Hoseini-Yazdi et al.21 (12.1 %), Magdalene et al.22 and Lara et al.19 (12.9 %).

The prevalence of convergence insufficiency (18.2 %) is more than the results found by Franco et al.33 although they used von Graefe method to assess the deviation. According to Cantó-Cerdán et al.,34 the von Graefe technique gives higher exophoric mean values than the cover test. Similar to our result, Magdalene et al.22 also reported convergence insufficiency (32 %) to be the most common NSBVA. Magdalene et al. also used the cover test method to assess horizontal phoria but their diagnostic criteria differed from ours which may cause greater prevalence than ours.

Unlike Daum, accommodative infacility (6.1 %) was found to be the most common accommodative dysfunction, followed by accommodative insufficiency (2.6 %). Daum's reported higher accommodative insufficiency in their clinical populations.35 He found that 96 subjects (80 %) showed accommodative insufficiency in his study of 114 subjects with accommodative dysfunctions. Daum's criteria for diagnosing accommodative insufficiency depended only on the measurement of accommodation amplitude. If other diagnostic signs are also taken into account, the outcome may differ. Larger the number of diagnostic signs used to diagnose a NSBVA, the lower the prevalence of the anomaly.[33] Scheiman et al.36 studied 2023 subjects of ages up to 18 year using more diagnostic sign and observed that 19.7 % showed NSBVA. The population studied in that study was younger than ours and the prevalence of accommodative insufficiency was found to be just 2 %.

This study included only those subjects who did not require any changes in refractive correction. This approach aligns with findings from most studies, which emphasize the importance of addressing refractive errors before diagnosing or managing NSBVA. García-Munoz et al.37 observed that 13 of 23 participants with NSBVA also had uncorrected refractive problems. Similarly, in the study of Franco et al.33 among 156 patients, 106 (68 %) were diagnosed with uncorrected refractive error. A special note should be made of the high prevalence rate of NSBVA found in this study when compared to previous studies, which may be related to the exclusion of change subjective refractive error.

In this study, symptom categories from García-Muñoz et al.2 were used. Headaches, followed by visual fatigue and asthenopia were the most commonly reported symptoms in our study, similar to the results that other authors have reported.2,9 Headache symptoms were more commonly observed in subjects diagnosed with convergence insufficiency. As expected, subjects diagnosed with accommodative excess experienced blurred vision more frequently. Similarly, blurred vision at near was significantly more common among those with accommodative insufficiency. It is essential to consider the presence of these dysfunctions (refractive, accommodative, and/or binocular) in a subject, as they may trigger the onset of this symptomatology. Therefore, it is necessary to address these dysfunctions to reduce the prevalence of visual symptoms.8

This study has several limitations as it was conducted in a hospital-based setting, the findings may not be directly applicable to the general population, given that patients seeking care at a tertiary eye hospital may have a higher prevalence of NSBVA. Future studies in a general population or a multicenter study should be carried out in order to provide more accurate prevalence data. Additionally, we did not use standardized symptom questionnaires for assessing NSBVA, which may impact the consistency and comparability of our findings. In the scientific literature there is only one validated questionnaire to collect the symptoms associated with visual dysfunctions, the Symptom Questionnaire for Visual Dysfunctions,38,39 but it has not been validated in the language of the study subjects. In order to overcome this limitation, the examiner asked the patient about the symptomatology in the anamnesis and the symptoms reported by the subject were classified according to the symptom categories described in the scientific literature. Lastly, the relatively small sample size may have limited the reliability of our results, suggesting that future research should aim to include larger samples to improve the accuracy of the findings.

ConclusionIt is the first prevalence study of non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies in Nepalese populations. It is essential to assess all accommodative and binocular parameters in order to arrive at a diagnosis of non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies. Differences in diagnostic criteria, type of population studied, study design, and sampling methods may be the main reasons for variations in the prevalence of non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies. The current study showed two-fifth of the symptomatic subjects have non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies. Convergence insufficiency was the most common dysfunctions presented in the hospital-based population, followed by accommodative infacility and fusional vergence dysfunction. Headaches, along with visual fatigue and asthenopia, were the most frequently reported symptoms in subjects with non-strabismic binocular vision anomalies. These dysfunctions can be successfully managed with vision therapy, prism prescription and optical correction if diagnosed early.

Sources of fundingNil.

Source(s) of supportNil.

Presentation at a meetingNil.

Nil

Nil.