Red laser therapy has recently gained attention as a potential myopia treatment in children. However, concerns regarding the safety of directing red laser at the fovea have raised caution. As a result, there is growing interest in identifying alternative, safer methods of red light administration for myopia control. This study investigated whether short-term exposure to red LED light induces ocular vascular changes similar to those previously reported with red laser exposure.

MethodsTwenty healthy adults (28 ± 5 years) participated in four experimental sessions each: (1) morning red LED exposure, (2) evening red LED exposure (both 5 minutes), (3) morning control, and (4) evening control. Red light (λ = 626 nm, irradiance = 0.11 mW/cm²) was delivered to the right eye using a Ganzfeld dome. Biometry, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and OCT angiography (OCTA) were performed at baseline and at 5, 30, and 60 minutes post-exposure. Changes were analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVAs.

ResultsThere were no significant differences in axial length, choroidal thickness, or perfusion density of the superficial or deep vascular complexes between red light exposure and control conditions at 5, 30, or 60 minutes in the morning or evening (P > 0.05 for all).

ConclusionFindings show that short-term exposure to red LED light does not induce significant transient changes in ocular vascular structures. While some studies have related short term choroidal thickening or increased blood flow to longer term myopia control efficacy, it cannot be concluded from the current study whether red LEDs would be effective.

Myopia is a leading cause of visual impairment affecting quality of life and presenting a significant socioeconomic burden.1–3 Estimates predict that by the year 2050, about 50 % of the world’s population will have myopia, among which 10 % will have high myopia.4 Excessive axial elongation is one of the primary characteristics in myopia, which is associated with retinal and choroidal thinning and scleral remodeling. However, the mechanisms by which the eye undergoes these changes remain unclear.2,5,6 Several optical and pharmaceutical myopia control approaches are now available and acknowledged for their ability to partially manage myopia progression.7

Red laser therapy, referred to as repeated low-level red-light therapy (RLRL or LLLT), has recently emerged as a myopia control modality.8–10 To date, over thirty clinical trials have been published demonstrating the effectiveness of red laser therapy in children for slowing myopia progression and axial elongation (for reviews, see11,12). Red laser therapy is administered through tabletop devices that emit 650 nm coherent beams via semiconductor lasers, with 0.35 to 2 mW energy. Several models of red laser devices are manufactured for myopia control and have been used in clinical trials, including Eyerising International and Sky-n1201.10,13 For myopia control treatment, children are instructed to use the device for 3 min twice a day separated by at least 4 hours, and at least six days a week. Reports show up to 69.4 % effectivity in slowing myopia progression and 76.6 % effectivity in slowing axial elongation, with some children experiencing axial length shortening.9,14–16 However, the mechanism of red laser therapy in myopia control has not yet been elucidated. Additionally, there are concerns that the high powered coherent light emitted from red laser devices approaches or exceeds maximum exposure limits, thereby presenting a risk of retinal damage with repeated long term use.17,18 Indeed, two recent reports describe retinal damage and reduction in cone density in children following red laser therapy.19,20

A potential mechanism of red laser therapy is via photobiomodulation, which has been extensively used in applications such as dermatology, wound healing, dentistry, pain management, and joint health.21–24 Photobiomodulation is a process by which light therapy, when administered using particular wavelengths at a certain power and duration, as described be the Arnt-Schulz law, elicits a beneficial cellular response.25,26 The optical window for photobiomodulation is in the range of red to near-infrared wavelengths (600–1400 nm). Cytochrome C, within the cellular membrane of the mitochondria, acts as the primary photo acceptor, initiating a cascade of events leading to increased ATP, stabilization of reactive oxygen species, and changes in calcium and nitrogen oxide.27,28 With respect to myopia control, red laser therapy may help to maintain vascular homeostasis, promote retinal mitochondrial activity, increase scleral fibroblast proliferation, and stimulate collagen production.29,30

Reports show that children undergoing red laser therapy demonstrate choroidal thickening, with significant changes occurring during the first 1–3 months of treatment. Studies have also investigated the immediate retinal and choroidal effects of red laser exposure. Yang et al.31 reported significant changes in retinal fovea perfusion density immediately after 3 min of red laser exposure in children; however, there were no changes in choroidal thickness. Swiatczak and Schaeffel investigated short-term effects of 10 min of exposure to red light delivered via LEDs, an incoherent light source, and observed axial shortening, which was greater in non-myopic participants compared to myopic participants.32 In the latter study, the authors speculated that the observed axial shortening, an indirect measure of choroidal thickening, induced from 10 min of red LED exposure suggests that a coherent laser light is not needed for choroidal thickening, and therefore, red LEDs may also be effective in slowing myopia in children, although this has not yet been tested.

There is interest to understand if red LEDs might be effective in slowing myopia, while serving as a safer alternative for retinal health than lasers. The goal of this study was to examine the short-term effects of red LED light exposure on axial length, choroidal thickness, and inner retinal vasculature in young adults and to determine if there is an influence of time-of-day. Transient ocular changes may suggest that red LED light exposure can induce beneficial effects on ocular tissue.

MethodsParticipantsHealthy young adults were recruited to participate in four experimental sessions each. Inclusion criteria were best corrected visual acuity of 20/25 or better, anisometropia and astigmatism less than 1.5 D, and no ocular disease. Participants with systemic diseases associated with ocular pathology, use of any anti-myopia treatment, or history of travel to a different time zone two weeks prior to the experiment were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Houston and procedures followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained after the purpose and risks of the study were explained.

Experimental protocolThe protocol is shown in Fig. 1. Participants first presented to the lab for screening, which included visual acuity, non-cycloplegic autorefraction (WAM-5000; Grand Seiko, grandseiko.com, five measurements were averaged for each eye), and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging (Spectralis, Heidleberg, Germany) to ensure the posterior choroid border was visible. Participants in which the spherical equivalent refraction was ≤ −0.5 D were classified as myopic, and −0.5 to +1.0 D were classified as emmetropic.

Protocol. At each of four experimental sessions, participants watched a distance television for 10 min and underwent baseline ocular measurements. They were exposed to either red light or continued to watch the distance television for 5 min. Ocular measurements were repeated immediately at 5, 30, and 60 min.

Each participant was then scheduled for four experimental sessions, at least 24 hours apart: (1) morning red LED exposure (5 min), (2) evening red LED exposure (5 min), (3) morning control, and (4) evening control. Morning sessions began at 9:00 am ± 30 min and evening sessions began at 5:00 pm ± 30 min for consistency of diurnal timing, and the order of conditions was randomized for each participant. Participants were asked to refrain from caffeine and vigorous exercise on the days of the experiment, as these have been shown to affect choroidal thickness.33

At each experimental session, participants first watched television at 4 m for 10 min to minimize effects of previous activities on ocular structures. After 10 min of distance viewing, ocular biometry and OCT and OCT-angiography (OCTA) scans were obtained for the right eye. The participant then underwent 5 min of red light exposure (treatment) or continued to watch the television for 5 min (control). Biometry and imaging were repeated immediately after the 5 min exposure, and again at 30 and 60 min.

Light specificationsSpectral distributions of the red LEDs and the room lights (control condition) were measured with an illuminance spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta - CL-500A) and are shown in Fig. 2. Red LEDs were measured using an integrating sphere radiometer (S142C sensor + PM100D console, thorlabs.com) positioned at the chinrest facing the ganzfeld (Table 1). Red light was delivered using a ganzfeld dome (Fig. 3A, ColorDome, Espion, Diagnostics, LLC). The dome consists of LEDs with a wavelength of 626 ± 10 nm, providing full field illumination. Retinal irradiance was calculated to be 0.11 mW/cm2, and the maximum permissible retinal irradiance was calculated to be 56.78 mW/cm2.

For the 5 min red LED exposure, participants were instructed to view into the ganzfeld dome without their refractive correction, similar to how the red lasers are viewed for myopia treatment (Fig. 3B). There was no target inside the dome, thereby minimizing any stimulus for accommodation. Room lights were turned off. For control conditions, participants simply continued to watch the television at distance following the baseline measures under room illumination (200 lx). While clinical trials commonly utilize a 3 min red laser exposure for myopia control, a 5 min exposure was used in this study to enhance the probability of observing short-term physiological effects measurable by biometry, OCT, and OCTA.

Ocular biometryOcular biometry was obtained using a low coherence optical biometer (LenStar; Haag-Streit, Koniz, Switzerland). Axial length was measured as the distance between cornea and retinal pigment epithelium. At least five measurements (SD ≤ 10 µm) were collected and averaged at each time point.

OCT image acquisition and analysisTo measure retinal and choroidal thickness, two high quality (>30 dB) OCT scans with enhanced depth imaging mode were obtained at each time point. The scan protocol included two six-line 30° radial OCT scans centered on the fovea (Fig. 4A and B). B-scan averaging was set at 16 frames. Axial OCT image digital resolution was 3.5 µm/pixel. For each participant, the first baseline image was set as the reference for subsequent scans. Scans were exported as “*.vol” files, and the images were processed using a custom written MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) program, which automatically segmented the internal limiting membrane, Bruch’s membrane, and the choroid-sclera boundary, as described previously.34,35 Briefly, the program uses a neural network trained using 10,798 manually segmented B-scans, on a Deeplabv3+ network based on a ResNet50.36,37 Images were adjusted for lateral magnification based on each participant’s corneal curvature, anterior chamber depth, lens thickness, and axial length by constructing a schematic eye based on these parameters. The distance from the inner limiting membrane to Bruch’s membrane was taken as retinal thickness and the distance from Bruch’s membrane to choroid-sclera interface was taken as choroidal thickness. Segmented images were inspected for errors and adjusted manually; of 640 scans analyzed, 53 scans (8.3%) required correction of the choroid-sclera border. The average thickness in the 1-mm diameter centered at the fovea for the six lines of each radial scan was calculated and averaged across the two scans at each time point.

(A) Representative infrared image showing six-line radial OCT scan centered on the fovea (green); (B) segmentation using automated software; (C) representative infrared image of the OCTA scan protocol; (D) superficial vascular complex; (E) deep vascular complex; red circles indicate the central 2 mm diameter used for analysis.

OCT-angiography (OCTA, Spectralis, Heidelberg, Germany) was used to image the inner retinal vasculature, which was then processed to calculate the vascular perfusion density in the retina. One high quality 10° x 10° scan (>30 dB) centered on fovea was obtained at each time point (Fig. 4C–E). Images of the superficial vascular complex (SVC) and deep vascular complex (DVC) were exported separately and processed using a custom MATLAB program, as described previously.38 The images were adjusted for lateral magnification based on ocular biometry for each participant. Retinal vascular perfusion density was measured as a proportion of the bright to dark pixels in the 1 mm radius region centered on fovea for the SVC and DVC.

Statistical analysisStatistical tests were performed using SPSS. The normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro-wilk test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted. Changes in axial length, retinal and choroidal thickness, and vascular perfusion density at SVC and DVC were compared based on two within-subject factors, time of the day (morning vs evening) and time point (baseline, 5, 30, and 60 min), using a repeated measures ANOVA. Post-hoc Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons were applied for significant main effects and interactions.

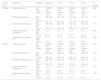

ResultsTwenty healthy young adults, ages 28.5 ± 4.6 years (13 females, 7 males), participated in four sessions each, two morning sessions (red light and control) and two evening sessions (red light and control). Mean spherical equivalent refraction was −0.81 ± 1.78 D (range −4.88 to +1.0 D), consisting of 7 myopes and 13 emmetropes. Axial length, choroidal thickness, and vascular perfusion density at the SVC and DVC at baseline, 5, 30, and 60 min are shown in Table 2. Baseline axial length was not significantly different between red light and control conditions (P = 0.14) or by time of day (P = 0.55). Baseline retinal thickness was not significantly different between red light and control conditions (P = 0.48). However, it was significantly greater by 1.4 ± 0.5 µm in the evening sessions compared to the morning sessions (P = 0.01), which can be attributed to expected diurnal variations.39 Similarly, baseline choroidal thickness was not significantly different between red light and control conditions (P = 0.46), but was significantly greater by 5.7 ± 2.4 µm in the morning sessions compared to the evening sessions (P = 0.03).

Axial length, retinal and choroidal thickness, and vascular perfusion density at the superficial and deep vascular complex at baseline, 5, 30, and 60 min (mean ± SD); N = 20 for all metrics except choroidal thickness, where N = 19.

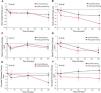

Changes in axial length for morning and evening sessions are shown in Fig. 5A and 5B There were no significant effects of red light on axial length change either in the morning or evening (P = 0.41) or at post-exposure time points compared to baseline (P = 0.42). Changes in retinal thickness for morning and evening sessions are shown in Fig. 5C and 5D There were no significant effects of red light on retinal thickness either in the morning or evening (P = 0.77) or at post-exposure time points compared to baseline (P = 0.61).

Changes from baseline over 60 min for A, B) axial length C, D) retinal thickness, E, F), choroidal thickness for control (black line) and red light (red line) in the morning (left column) and evening (right column). Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean. P-values represent statistical comparisons between experimental conditions and time of day.

The choroid-sclera boundary was not well-defined for one of the participants. Therefore, changes in choroidal thickness are presented for 19 participants (Fig. 5E and 5F). There were no significant effects of red light on choroidal thickness either in the morning or evening (P = 0.31) or at post-exposure time points compared to baseline (P = 0.10).

Changes in superficial vascular complex for morning and evening sessions are shown in Fig. 6A and 6B There were no significant effects of red light on vascular perfusion density in the superficial vascular complex either in the morning or evening (P = 0.95) or at post-exposure time points compared to baseline (P = 0.10).

Changes from baseline over 60 min for A, B) the superficial vascular complex, and C, D) the deep vascular complex for control (black line) and red light (red line) in the morning (left column) and evening (right column). Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean. P-values represent statistical comparisons between experimental conditions and time of day.

Changes in the deep vascular complex for morning and evening sessions are shown in Fig. 6C and 6D There were no significant effects of red light on vascular perfusion density in the deep vascular complex either in the morning or evening (P = 0.86) or at post-exposure time points compared to baseline (P = 0.36).

DiscussionThis study investigated the ocular effects of 5 min of diffuse red LED light exposure in healthy young adults at different times of the day. Our findings demonstrate that 5 min of exposure to red LED light does not cause significant changes in retinal or choroidal thickness or retinal vascular perfusion density in the morning or in the evening.

Previous studies using red laser therapy, typically 650 nm laser light for 3 min, have reported transient alterations in ocular parameters. Yang et al. reported a significant 2 % increase in foveal perfusion density following a single exposure of 3 min to the red laser in children,31 with no changes in retinal thickness. The absence of methodological details regarding OCTA image analysis limits the ability to directly compare their retinal perfusion density findings with the current study. Another study reported macular retinal thickening one month after initiating red laser therapy for myopia.40

Apart from retinal thickness and perfusion changes, exposure to red lasers has been shown to increase choroidal thickness, with a peak effect occurring during the first 1–3 months of treatment.41–45 Liu et al. observed an increase in choroidal vascular volume and reduced axial length progression over 12 months.46 On the other hand, Yang et al. found no significant choroidal thickness change following a single 3-minute laser session, suggesting that cumulative exposure may be necessary to achieve measurable anatomical effects on the choroid.31 Therefore, increases in choroidal thickness and other choroidal parameters could possibly be a result of repeated exposures over time. However, given that the laser devices for myopia may exceed safe levels of exposure, it is possible that the observed increases in retinal and choroidal thickness may reflect an inflammatory or phototoxic response.17

A key difference between previous studies examining coherent red lasers for myopia is that our study utilized an incoherent LED light source rather than a laser, as concerns exist with the use of lasers in myopia control instruments.17 Different sources of light vary in their impact on retinal illuminance, influencing the amount of light reaching and interacting with retina.47 Bochenek et al. used 20 min of red LED exposure (625 ± 17 nm, 1000 lx) and showed no immediate changes in axial length in young adults, consistent with the findings of the current study.48 In contrast, Swiatczak and Schaeffel reported a decrease in axial length following 10 min of exposure to LED light source through a red filter (620 ± 10 nm, 0.25 mW/cm2); the ocular effects in the latter study were observed only in non-myopic participants.32 On the other hand, clinical trials have laser devices of power ranging from 0.1 to 2 mW and a peak wavelength of 635–650 nm.9,10,13–15,41,44,45,49–60 Our study utilized a power source of 0.57 mW and a peak wavelength of 626 ± 10 nm. Considering the differences in power and wavelength of red light used in these studies, the observed discrepancies may be attributed to variations in the amount of light energy reaching the posterior ocular structures, as well as differences in measurement techniques for axial length, choroidal thickness, and retinal perfusion.

Two previous studies examined choroidal thickness after one hour of red LED exposure in young adults.61,62 Both studies reported that the choroid underwent significant thinning in red light. This is in contradiction to the hypothesis that exposures thought to be protective for myopia, such as red light, would induce short term choroidal thickening.63 Taken together, evidence from these previous studies suggests that short term choroidal thickening is not necessary for a particular exposure to have long term efficacy in slowing myopia.

Tissue hypoxia has been proposed as one of the major factors that drives changes in the extracellular matrix of sclera during myopic axial elongation.64–66 The choroid, which is located between the retina and sclera, supplies nutrients and oxygen to the outer retina and to the sclera. Evidence from animal models undergoing experimental myopia show that the choroid thins with myopia.67 It has been also observed that choroidal thinning due to reduced choroidal blood perfusion results in myopic shifts in refraction and hypoxia-related changes in the choroid and sclera.68 Since red light enhances metabolic activity within tissues,29 it is plausible that red light therapy may promote retinal and choroidal blood flow, alleviating tissue hypoxia. This, in turn, could play a role in regulating scleral remodeling associated with myopia. While increases in retinal perfusion and choroidal thickness were not observed here with a single 5 min exposure to red LEDs, repeated exposure over a longer period may produce a significant effect.

Species related differences have been observed in the effects of red light exposure on eye growth and experimental myopia in various animal modes. When reared in red light, rhesus monkeys69 and tree shews70 became more hyperopic, whereas chickens71 and guinea pigs72 became myopic. Animal studies typically use 12 hours per day of red LED exposure, in contrast to red laser therapy for children, which uses 6 min per day of red laser exposure. While the mechanisms underlying red light’s effects remain unclear, evidence from photobiomodulation with low level light therapy, which is widely used in dermatological applications, indicates that tissue absorbs the light and translate the signals into metabolic changes.25,29

The primary objective of our study was to investigate the immediate ocular responses to red light therapy and assess whether the time of day influences these effects. There are a few limitations to the study. First, adults were included in our experiment, similar to previous short term studies on the immediate effects of red light,32,73 whereas red light therapy for myopia is intended for children.74–77 While red light therapy applications outside myopia control have demonstrated efficacy across age groups, including for age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and several other ocular conditions,78–80 age related differences may have influenced our findings. Second, the calculated retinal irradiance of the light used in our study (0.11 mW/cm2) was lower than that are commercially available (0.1–100 W/cm2), which may have further influenced the lack of an ocular response.17 Third, our study was not powered to conduct analyses based on refractive error group. Future studies with a larger sample of myopes and non-myopes will be needed to address potential refractive error differences.

Another limitation is that ocular measurements were taken after a single 5-minute exposure to diffuse red LED light. Longitudinal studies with repeated exposures are needed to better understand cumulative effects. The Arndt-Schultz law suggests that weak stimuli enhance vital activity while a stronger stimuli amplify it until a peak is reached, beyond which excessive stimulation suppresses cellular function leading to tissue inhibition.81 In the current study, the diffuse red LED of 0.11 mW/cm2 may have been lower than that of the sensitive region. A key limitation in comparing our findings with previous clinical trials is the lack of standardized reporting of retinal light dose. While our study quantified retinal irradiance, most trials using laser-based devices report only the nominal power output of the light source.9,10,13–15,41,44,45,49–60

Despite these limitations, this study is pivotal because it establishes the lack of an immediate ocular response to single-dose diffuse red light at different times of day, data that define baseline variability, reveal early dose–response relationships, including time of day changes. This foundational insight is especially important given that some red laser devices may exceed safe exposure limits. By measuring the immediate effects of low irradiance, incoherent LED light, our study captured the short-term changes needed before developing safe, long-term myopia control treatments. In conclusion, this study shows that 5 min of diffuse red LED exposure is not sufficient to elicit acute ocular changes in retinal or choroidal thickness or inner retinal perfusion. Future studies are warranted to examine the relationship between the ocular response and different intensities and durations of red light to better understand its protective effects in myopia progression.

FundingNIH R01EY030193.

Authors’ contributionsJJP: Conception and design, Data collection, Analysis and interpretation, Drafting the manuscript and critical revision; Ostrin LA: Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation, critical revision.

DisclosuresJJP: none; LAO: Zeiss, Essilor, Alcon (consulting), Meta, Topcon (research support), Patent (US 11,375,890 B2)