This review aimed to estimate the prevalence of computer vision syndrome (CVS) in the general population and subgroups.

MethodsA search was conducted in the following the databases: PubMed, SCOPUS, EMBASE, and Web of Science until February 13, 2023. We included studies that assessed the prevalence of CVS in any population. The Joanna Briggs Institute's critical appraisal tool was used to evaluate the methodological quality. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of CVS was done using a random-effects model, assessing the sources of heterogeneity using subgroup and meta-regression analyses.

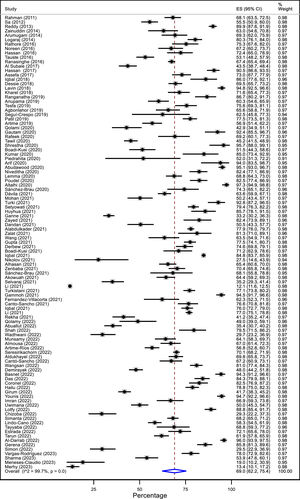

ResultsA total of 103 cross-sectional studies with 66 577 participants were included. The prevalence of CVS was 69.0% (95% CI: 62.3 to 75.3; I2: 99.7%), ranging from 12.1 to 97.3% across studies. Point prevalence was higher in women than in men (71.4 vs. 61.8%), university students (76.1%), Africa (71.2%), Asia (69.9%), contact lens wearers (73.1% vs. 63.8%) in studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic (72.8%), and in those that did not use the CVS-Q questionnaire (75.4%). In meta-regression, using the CVS-Q scale was associated with a lower prevalence of CVS.

ConclusionSeven out of ten people suffer from CVS. Preventive strategies and interventions are needed to decrease the prevalence of this condition which can affect productivity and quality of life. Future studies should standardize a definition of CVS.

In the last two decades, the usage of technological devices has rapidly increased, allowing accelerated advances in globalization, improved access to information, more significant work efficiency, and ease of communication.1,2 However, this massive phenomenon affects the eye health of the general population by developing signs and symptoms that collectively are so-called computer vision syndrome (CVS).3 The American Optometric Association (AOA) defines it as a set of visual disturbances resulting from prolonged use of video display terminals (VDTs), such as computers, tablets, e-readers, and cell phones.4 CVS includes ocular symptoms such as eye fatigue, irritated/dry eyes, presbyopia, and blurred vision, among others associated with accommodation; extraocular symptoms such as the neck, shoulder, and back pain associated with posture and position for computer use.5,6

The prevalence of CVS is highly variable, with globally reported data ranging from 12.1% to 94.8% in the pediatric population and from 35.2% to 97.3% in the adult population.7–10 The prevalence varies according to the evaluated demographic data (sex, age group, place of origin, occupation). CVS presents risk factors that increase the probability of developing it, such as contact lenses use, psychological stress, previous visual pathologies, use of multiple VDTs, and technological addiction problems.11,12 Another factor that could modify prevalence is the operational definition of CVS across studies, with the Computer Vision Syndrome - questionnaire (CVS-Q)13 being the most commonly used questionnaire. In addition, during the COVID-19 pandemic, this syndrome may have increased due to the increased use of VDTs during social isolation14,15 and the lack of timely ophthalmologic care owing to pandemic-related consultation constraints.16

It is necessary to know the prevalence of CVS in the general population and how it varies according to subgroups such as sex, and method of diagnosis, among others. These data will allow us to understand the problem and identify the most affected groups to formulate prevention and treatment policies. Therefore, this systematic review with meta-analysis aimed to estimate the prevalence of CVS in the general population. Secondarily, we analyzed the prevalence by subgroups.

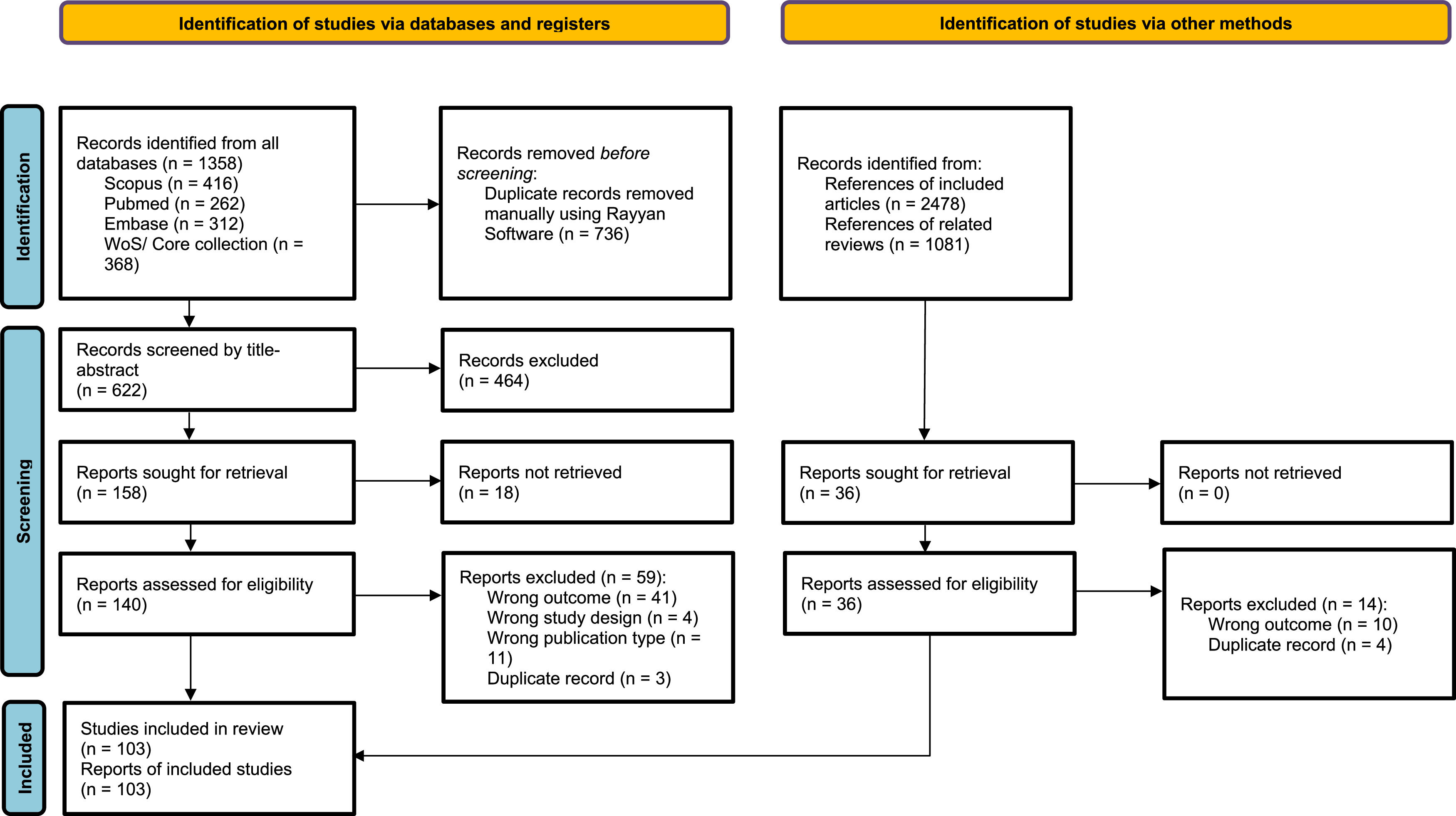

Material and methodsThe study protocol was registered in the PROSPERO platform (CRD42022300390). The report was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines.17

Eligibility criteriaCross-sectional and cohort studies that reported the prevalence of CVS in general population (no age or occupation restrictions) were included. Studies that defined CVS as a set of eye and vision-related symptoms resulting from prolonged use of computers, tablets, e-readers, and cell phones were incorporated. Studies that mentioned textually that they were evaluating CVS or digital eye strain were included. For the operational definition, a particular definition was not considered and studies that assessed CVS with validated (e.g., CVS-Q) and nonvalidated (e.g., at least one symptom present) methods were included. Randomized clinical trials, case-control studies, case reports, opinions, reviews, conference abstracts and studies not available in the full text were excluded.

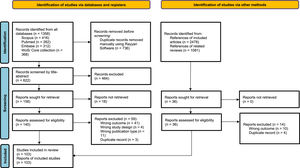

Literature search and study selectionSearches were conducted in the following databases: 1) PubMed, 2) SCOPUS, 3) EMBASE, and 4) Web of Science/Core collection on February 13, 2023. No language or publication date restrictions were applied. For the search strategy, we used the terms: computer vision syndrome, computer visual syndrome, and digital eye strain. The complete strategy for each database can be found in supplementary material 1. In addition, we reviewed the bibliographic references of the identified reviews and contained studies to find potentially eligible studies. Duplicate articles were manually removed with Rayyan software.18 Two authors (KGT and JNNL) independently reviewed titles and abstracts potentially eligible for selection; discrepancies were resolved with a third author (FCB). Subsequently, studies were reviewed in full-text and independently by four authors (FBC and SDCD reviewed a half, DRSM, and FCB reviewed other half) with the participation of a diriment author (DRSM) to discuss discordances and reach a consensus.

Data extractionThe interest data were extracted independently by four authors (FBC, SDCD, KGT, and JNNL) in a Microsoft Excel sheet. The discordances found were resolved with a single author (FCB). The variables of interest extracted from each study were: first author, year of publication, continent, country, study design, country income level, type of population studied (general population, children, workers, and students), the time of VDT use, the use of contact lenses, whether patients with ophthalmic pathology were excluded, whether the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, sample size, population characteristics (age and sex), symptoms included in the diagnostic criteria for CVS as well as the criteria for defining it, the prevalence in the whole population and according to sex. Data presented as median and interquartile range were converted to mean with standard deviation.

Risk of biasTwo authors (DRSM and KGT) independently assessed the methodological quality of prevalence studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute's critical appraisal tool19,20 using Microsoft Excel software. A third author (FCB) resolved discrepancies in this process. This scale has nine items with possible responses of yes, no, and unclear. The quality score was considered as one point for yes and zero points for no and unclear. The methodological quality of the studies was classified as low risk of bias (7 or more points), moderate risk of bias (4 to 6 points), and high risk of bias (less than 4 points).

Statistical analysesThe analysis was performed with the Stata/SE version 16 program (Stata Corp, Texas, USA). Following our protocol, studies that reported the value of CVS prevalence in its study population in the meta-analysis were included. For the latter, pooled prevalences using a random-effects model were calculated, with their 95% confidence intervals calculated using the exact method. The Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was used to stabilize variances. The I² statistic was used to assess heterogeneity and considered an I² ≥ 40% as heterogeneity present.21 A meta-analysis was also performed by subgroups according to sex, continent, country income level, type of population, diagnostic criteria, whether the study was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether patients with ophthalmologic symptoms or diseases were included, and risk of bias. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of articles with adequate sample sizes (n>384). Publication bias was evaluated through the funnel plot and statistically using Egger's test, considering as significant a p<0.1. Finally, as a post hoc analysis, to explore heterogeneity, a multivariate meta-regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of the following variables: age, sex, continent, country income level, type of population, diagnostic criteria, whether the study was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether were included patients with symptoms or ophthalmologic diseases, risk of bias, publication year, mean VDTs hours of use, and% of patients with contact lenses in the study population.

ResultsStudy selectionAfter eliminating duplicates, the title and abstract of 622 articles were evaluated. From the latter, 176 studies were reviewed in full text, and 103 were finally included7–11,15,22–118 (Fig. 1). The reasons for excluding full-text articles are given in supplementary material 2.

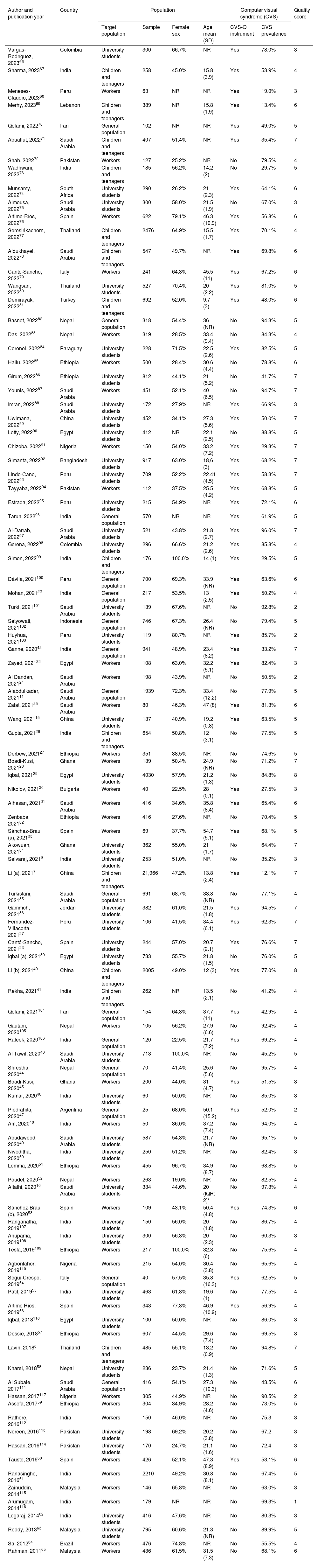

Study characteristicsTable 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. The 103 included studies were cross-sectional. The study sample size ranged from 2547 to 21 9667 individuals, with a total of 66 577 participants. Regarding the continent, 62 were conducted in Asia, 21 in Africa, 11 in Latin America, and 9 in Europe. The mean age of participants ranged from 9.7 to 54.7 years. Regarding populations, 37 studies evaluated workers (mainly office, informatic workers, or university workers), 38 university students, 14 children and adolescents, and the rest general population. The studies by Gerena, et al., Al Tawil et al., and Tesfa et al. included only women.43,98,109 Forty eight studies (46.6%) were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, 45 (43.7%) articles excluded participants with ophthalmologic pathologies.

Characteristics of the included studies (n = 103).

| Author and publication year | Country | Population | Computer visual syndrome (CVS) | Quality score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population | Sample | Female sex | Age mean (SD) | CVS-Q instrument | CVS prevalence | |||

| Vargas-Rodríguez, 202366 | Colombia | University students | 300 | 66.7% | NR | Yes | 78.0% | 3 |

| Sharma, 202367 | India | Children and teenagers | 258 | 45.0% | 15.8 (3.9) | Yes | 53.9% | 4 |

| Meneses-Claudio, 202368 | Peru | Workers | 63 | NR | NR | Yes | 19.0% | 3 |

| Merhy, 202369 | Lebanon | Children and teenagers | 389 | NR | 15.8 (1.9) | Yes | 13.4% | 6 |

| Qolami, 202270 | Iran | General population | 102 | NR | NR | Yes | 49.0% | 5 |

| Abuallut, 202271 | Saudi Arabia | Children and teenagers | 407 | 51.4% | NR | Yes | 35.4% | 7 |

| Shah, 202272 | Pakistan | Workers | 127 | 25.2% | NR | No | 79.5% | 4 |

| Wadhwani, 202273 | India | Children and teenagers | 185 | 56.2% | 14.2 (2) | No | 29.7% | 5 |

| Munsamy, 202274 | South Africa | University students | 290 | 26.2% | 21 (2.3) | Yes | 64.1% | 6 |

| Almousa, 202275 | Saudi Arabia | University students | 300 | 58.0% | 21.5 (1.9) | No | 67.0% | 3 |

| Artime-Ríos, 202276 | Spain | Workers | 622 | 79.1% | 46.3 (10.9) | Yes | 56.8% | 6 |

| Seresirikachorn, 202277 | Thailand | Children and teenagers | 2476 | 64.9% | 15.5 (1.7) | Yes | 70.1% | 4 |

| Aldukhayel, 202278 | Saudi Arabia | Children and teenagers | 547 | 49.7% | NR | Yes | 69.8% | 6 |

| Cantó-Sancho, 202279 | Italy | Workers | 241 | 64.3% | 45.5 (11) | Yes | 67.2% | 6 |

| Wangsan, 202280 | Thailand | University students | 527 | 70.4% | 20 (2.2) | Yes | 81.0% | 5 |

| Demirayak, 202281 | Turkey | Children and teenagers | 692 | 52.0% | 9.7 (3) | Yes | 48.0% | 6 |

| Basnet, 202282 | Nepal | General population | 318 | 54.4% | 36 (NR) | No | 94.3% | 5 |

| Das, 202283 | Nepal | Workers | 319 | 28.5% | 33.4 (9.4) | No | 84.3% | 4 |

| Coronel, 202284 | Paraguay | University students | 228 | 71.5% | 22.5 (2.6) | Yes | 82.5% | 5 |

| Hailu, 202285 | Ethiopia | Workers | 500 | 28.4% | 30.6 (4.4) | No | 78.8% | 6 |

| Girum, 202286 | Ethiopia | University students | 812 | 44.1% | 21 (5.2) | No | 41.7% | 7 |

| Younis, 202287 | Saudi Arabia | Workers | 451 | 52.1% | 40 (6.5) | No | 94.7% | 7 |

| Imran, 202288 | Saudi Arabia | University students | 172 | 27.9% | NR | Yes | 66.9% | 3 |

| Uwimana, 202289 | China | University students | 452 | 34.1% | 27.3 (5.6) | Yes | 50.0% | 7 |

| Lotfy, 202290 | Egypt | University students | 412 | NR | 22.1 (2.5) | No | 88.8% | 5 |

| Chizoba, 202291 | Nigeria | Workers | 150 | 54.0% | 33.2 (7.2) | Yes | 29.3% | 7 |

| Simanta, 202292 | Bangladesh | University students | 917 | 63.0% | 18,6 (3) | Yes | 68.2% | 7 |

| Lindo-Cano, 202293 | Peru | University students | 709 | 52.2% | 22.41 (4.5) | Yes | 58.3% | 7 |

| Tayyaba, 202294 | Pakistan | Workers | 112 | 37.5% | 25.5 (4.2) | Yes | 68.8% | 5 |

| Estrada, 202295 | Peru | University students | 215 | 54.9% | NR | Yes | 72.1% | 6 |

| Tarun, 202296 | India | General population | 570 | NR | NR | Yes | 61.9% | 5 |

| Al-Darrab, 202297 | Saudi Arabia | University students | 521 | 43.8% | 21.8 (2.7) | Yes | 96.0% | 7 |

| Gerena, 202298 | Colombia | University students | 296 | 66.6% | 21.2 (2.6) | Yes | 85.8% | 4 |

| Simon, 202299 | India | Children and teenagers | 176 | 100.0% | 14 (1) | Yes | 29.5% | 5 |

| Dávila, 2021100 | Peru | General population | 700 | 69.3% | 33.9 (NR) | Yes | 63.6% | 6 |

| Mohan, 202122 | India | General population | 217 | 53.5% | 13 (2.5) | Yes | 50.2% | 4 |

| Turki, 2021101 | Saudi Arabia | University students | 139 | 67.6% | NR | No | 92.8% | 2 |

| Setyowati, 2021102 | Indonesia | General population | 746 | 67.3% | 26.4 (NR) | No | 79.4% | 5 |

| Huyhua, 2021103 | Peru | University students | 119 | 80.7% | NR | Yes | 85.7% | 2 |

| Ganne, 202042 | India | General population | 941 | 48.9% | 23.4 (8.2) | Yes | 33.2% | 7 |

| Zayed, 202123 | Egypt | Workers | 108 | 63.0% | 32.2 (5.1) | Yes | 82.4% | 3 |

| Al Dandan, 202124 | Saudi Arabia | Workers | 198 | 43.9% | NR | No | 50.5% | 2 |

| Alabdulkader, 202111 | Saudi Arabia | General population | 1939 | 72.3% | 33.4 (12.2) | No | 77.9% | 5 |

| Zalat, 202125 | Saudi Arabia | Workers | 80 | 46.3% | 47 (8) | Yes | 81.3% | 6 |

| Wang, 202115 | China | University students | 137 | 40.9% | 19.2 (0.8) | Yes | 63.5% | 5 |

| Gupta, 202126 | India | Children and teenagers | 654 | 50.8% | 12 (3.1) | No | 77.5% | 5 |

| Derbew, 202127 | Ethiopia | Workers | 351 | 38.5% | NR | No | 74.6% | 5 |

| Boadi-Kusi, 202128 | Ghana | Workers | 139 | 50.4% | 24.9 (NR) | No | 71.2% | 7 |

| Iqbal, 202129 | Egypt | University students | 4030 | 57.9% | 21.2 (1.3) | No | 84.8% | 8 |

| Nikolov, 202130 | Bulgaria | Workers | 40 | 22.5% | 28 (0.1) | Yes | 27.5% | 3 |

| Alhasan, 202131 | Saudi Arabia | Workers | 416 | 34.6% | 35.8 (8.4) | Yes | 65.4% | 6 |

| Zenbaba, 202132 | Ethiopia | Workers | 416 | 27.6% | NR | No | 70.4% | 5 |

| Sánchez-Brau (a), 202133 | Spain | Workers | 69 | 37.7% | 54.7 (5.1) | Yes | 68.1% | 5 |

| Akowuah, 202134 | Ghana | University students | 362 | 55.0% | 21 (1.7) | No | 64.4% | 7 |

| Selvaraj, 20219 | India | University students | 253 | 51.0% | NR | No | 35.2% | 3 |

| Li (a), 20217 | China | Children and teenagers | 21,966 | 47.2% | 13.8 (2.4) | Yes | 12.1% | 7 |

| Turkistani, 202135 | Saudi Arabia | General population | 691 | 68.7% | 33.8 (NR) | No | 77.1% | 4 |

| Gammoh, 202136 | Jordan | University students | 382 | 61.0% | 21.5 (1.8) | Yes | 94.5% | 7 |

| Fernandez-Villacorta, 202137 | Peru | University students | 106 | 41.5% | 34.4 (6.1) | Yes | 62.3% | 7 |

| Cantó-Sancho, 202138 | Spain | University students | 244 | 57.0% | 20.7 (2.1) | Yes | 76.6% | 7 |

| Iqbal (a), 202139 | Egypt | University students | 733 | 55.7% | 21.8 (1.5) | No | 76.0% | 5 |

| Li (b), 202140 | China | Children and teenagers | 2005 | 49.0% | 12 (3) | Yes | 77.0% | 8 |

| Rekha, 202141 | India | Children and teenagers | 262 | NR | 13.5 (2.1) | No | 41.2% | 4 |

| Qolami, 2021104 | Iran | General population | 154 | 64.3% | 37.7 (11) | Yes | 42.9% | 4 |

| Gautam, 2020105 | Nepal | Workers | 105 | 56.2% | 27.9 (6.6) | No | 92.4% | 4 |

| Rafeek, 2020106 | India | General population | 120 | 22.5% | 21.7 (7.2) | Yes | 69.2% | 4 |

| Al Tawil, 202043 | Saudi Arabia | University students | 713 | 100.0% | NR | No | 45.2% | 5 |

| Shrestha, 202044 | Nepal | General population | 70 | 41.4% | 25.6 (5.6) | No | 95.7% | 4 |

| Boadi-Kusi, 202045 | Ghana | Workers | 200 | 44.0% | 31 (4.7) | Yes | 51.5% | 3 |

| Kumar, 202046 | India | University students | 60 | 50.0% | NR | No | 85.0% | 3 |

| Piedrahita, 202047 | Argentina | General population | 25 | 68.0% | 50.1 (15.2) | Yes | 52.0% | 2 |

| Arif, 202048 | India | Workers | 50 | 36.0% | 37.2 (7.4) | No | 94.0% | 4 |

| Abudawood, 202049 | Saudi Arabia | University students | 587 | 54.3% | 21.7 (NR) | No | 95.1% | 5 |

| Niveditha, 202050 | India | University students | 250 | 51.2% | NR | No | 82.4% | 3 |

| Lemma, 202051 | Ethiopia | Workers | 455 | 96.7% | 34.9 (8.7) | No | 68.8% | 5 |

| Poudel, 202052 | Nepal | Workers | 263 | 19.0% | NR | No | 82.5% | 4 |

| Altalhi, 202010 | Saudi Arabia | University students | 334 | 44.6% | 20 (IQR: 2)* | No | 97.3% | 4 |

| Sánchez-Brau (b), 202053 | Spain | Workers | 109 | 43.1% | 50.4 (4.8) | Yes | 74.3% | 6 |

| Ranganatha, 2019107 | India | University students | 150 | 56.0% | 20 (1.8) | No | 86.7% | 4 |

| Anupama, 2019108 | India | University students | 300 | 56.3% | 20 (2.3) | No | 60.3% | 3 |

| Tesfa, 2019109 | Ethiopia | Workers | 217 | 100.0% | 32.3 (6) | No | 75.6% | 4 |

| Agbonlahor, 2019110 | Nigeria | Workers | 215 | 54.0% | 30.4 (3.8) | No | 65.6% | 4 |

| Seguí-Crespo, 201954 | Italy | General population | 40 | 57.5% | 35.8 (16.3) | Yes | 62.5% | 5 |

| Patil, 201955 | India | University students | 463 | 61.8% | 19.6 (1) | No | 77.5% | 4 |

| Artime Ríos, 201956 | Spain | Workers | 343 | 77.3% | 46.9 (10.9) | Yes | 56.9% | 4 |

| Iqbal, 2018118 | Egypt | University students | 100 | 50.0% | NR | No | 86.0% | 3 |

| Dessie, 201857 | Ethiopia | Workers | 607 | 44.5% | 29.6 (7.4) | No | 69.5% | 8 |

| Lavin, 20188 | Thailand | Children and teenagers | 485 | 55.1% | 13.2 (0.9) | No | 94.8% | 7 |

| Kharel, 201858 | Nepal | University students | 236 | 23.7% | 21.4 (1.3) | No | 71.6% | 5 |

| Al Subaie, 2017111 | Saudi Arabia | General population | 416 | 54.1% | 27.3 (10.3) | No | 43.5% | 6 |

| Hassan, 2017117 | Nigeria | Workers | 305 | 44.9% | NR | No | 90.5% | 2 |

| Assefa, 201759 | Ethiopia | Workers | 304 | 34.9% | 28.2 (4.6) | No | 73.0% | 5 |

| Rathore, 2016112 | India | Workers | 150 | 46.0% | NR | No | 75.3 | 3 |

| Noreen, 2016113 | Pakistan | University students | 198 | 69.2% | 20.2 (3.8) | No | 67.2 | 3 |

| Hassan, 2016114 | Pakistan | University students | 170 | 24.7% | 21.1 (1.6) | No | 72.4 | 3 |

| Tauste, 201660 | Spain | Workers | 426 | 52.1% | 47.3 (8.9) | Yes | 53.1% | 6 |

| Ranasinghe, 201661 | India | Workers | 2210 | 49.2% | 30.8 (8.1) | No | 67.4% | 5 |

| Zainuddin, 2014115 | Malaysia | Workers | 146 | 65.8% | NR | No | 63.0% | 3 |

| Arumugam, 2014116 | India | Workers | 179 | NR | NR | No | 69.3% | 1 |

| Logaraj, 201462 | India | University students | 416 | 47.6% | NR | No | 80.3% | 3 |

| Reddy, 201363 | Malaysia | University students | 795 | 60.6% | 21.3 (NR) | No | 89.9% | 5 |

| Sa, 201264 | Brazil | Workers | 476 | 74.8% | NR | No | 55.5% | 4 |

| Rahman, 201165 | Malaysia | Workers | 436 | 61.5% | 31.5 (7.3) | No | 68.1% | 6 |

Abbreviations: CVS (Computer visual syndrome); CVS-Q (Computer Vision Syndrome Questionnaire); SD (Standard deviation); NR: not reported.

*Median (interquartile range).

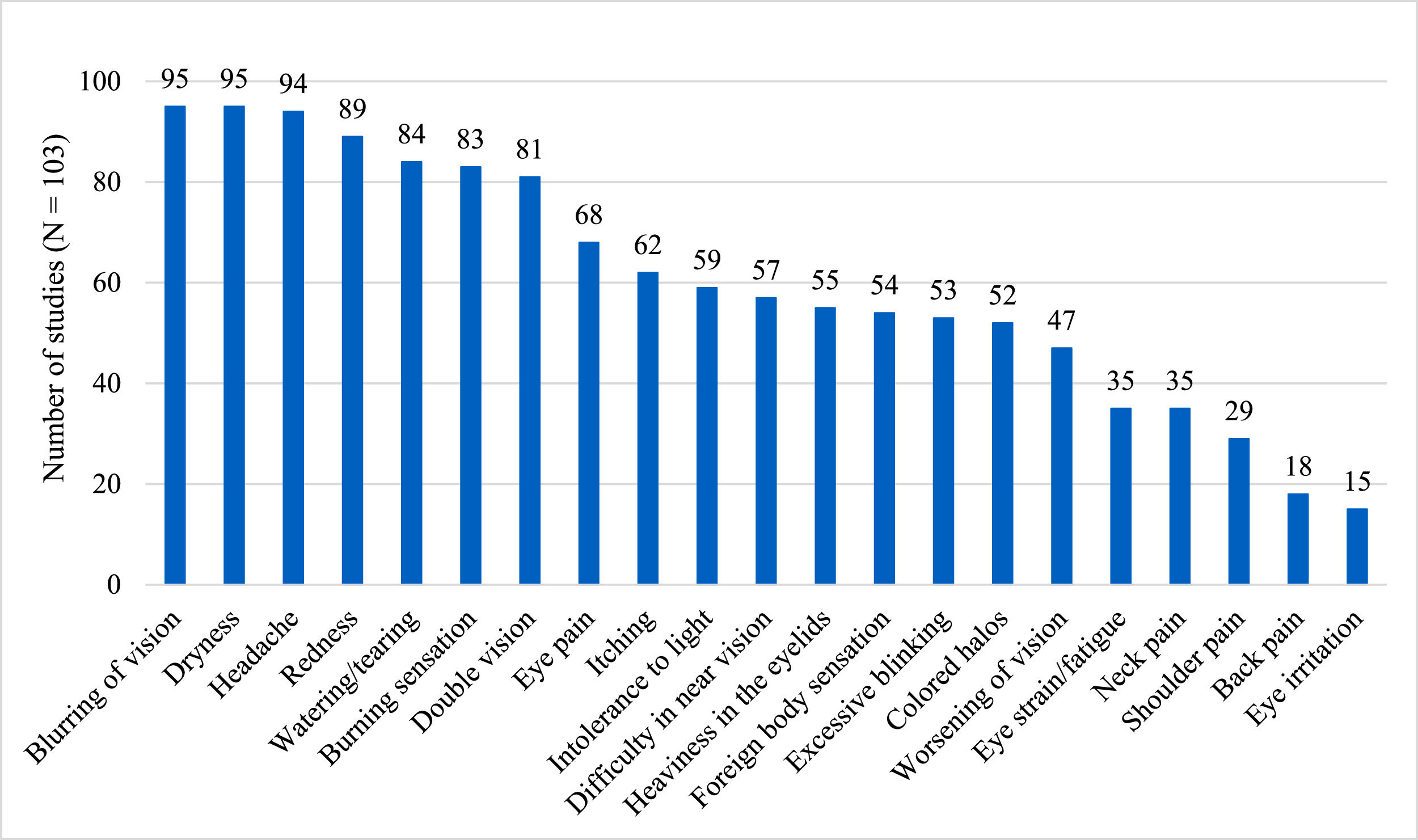

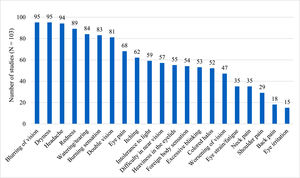

As a diagnostic method, 49 studies used the CVS-Q, which diagnoses patients with a score ≥6 points with CVS.13 Iqbal et al. (a) used the CVS-F3 scale, which is not validated and defines CVS as the presence of at least one symptom.29 The remaining 54 studies did not use any validated tool and defined CVS as having at least one or more symptoms. The most frequently used ophthalmologic symptoms to diagnose CVS among the studies were: blurring of vision (92%), dryness (92%), and redness (86%). In addition, some studies considered extraocular symptoms such as headache (91%), neck pain (34%), shoulder pain (28%), and back pain (17%) (Fig. 2). Other symptoms evaluated were finger pain, tired eyes, insomnia, depression, joint pain, numbness of hands, and general discomfort (see supplementary material 3). The median number of symptoms used to define CVS across studies was 12.9 (IQR: 9 to 16) symptoms.

Risk of biasMost studies described the population adequately and measured the condition reliably for all participants. On the other hand, 38.9% did not comply with achieving an adequate sampling or having an adequate sample, which could affect the representativeness of the data. In addition, less than half (47.6%) used an adequate sampling frame (low number of studies in the community), performed an appropriate statistical analysis (25.2%), and measured CVS with validated methods (47.6%). The overall risk of bias assessment score is in Table 2, and its detailed assessment is in supplementary material 4.

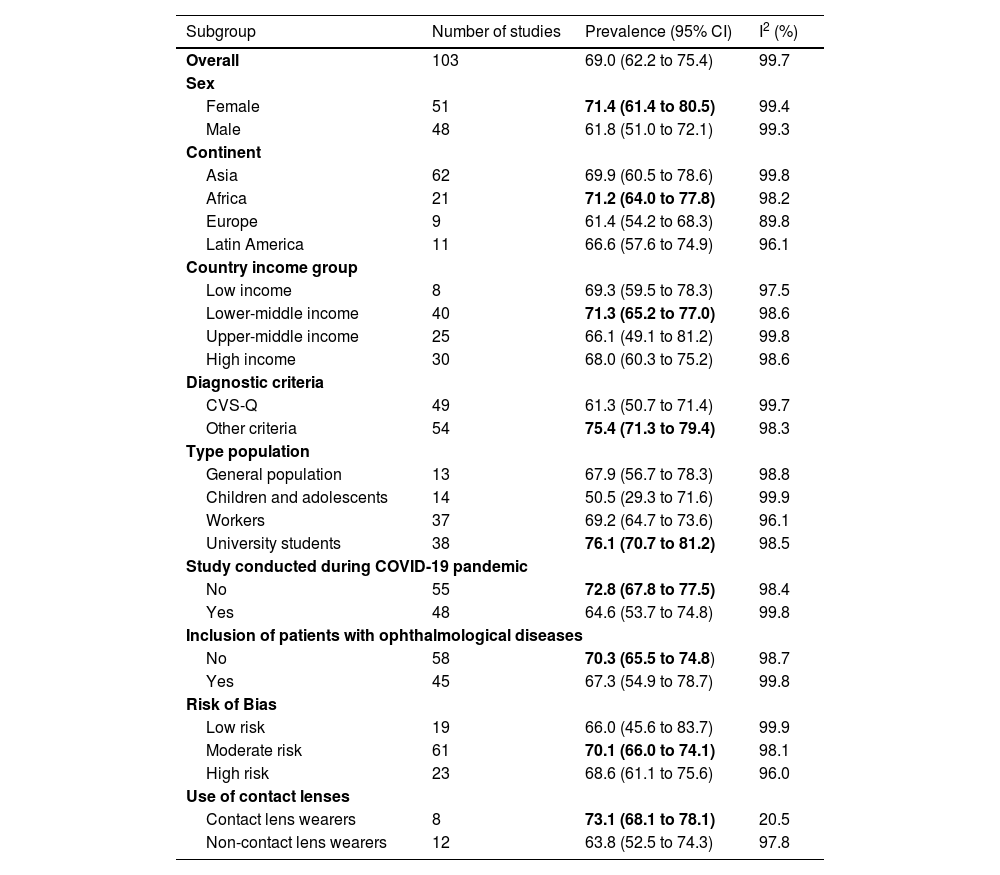

Overall and subgroups prevalence of computer vision syndrome.

CI: Confidence interval; CVS-Q: Computer vision syndrome questionnaire.

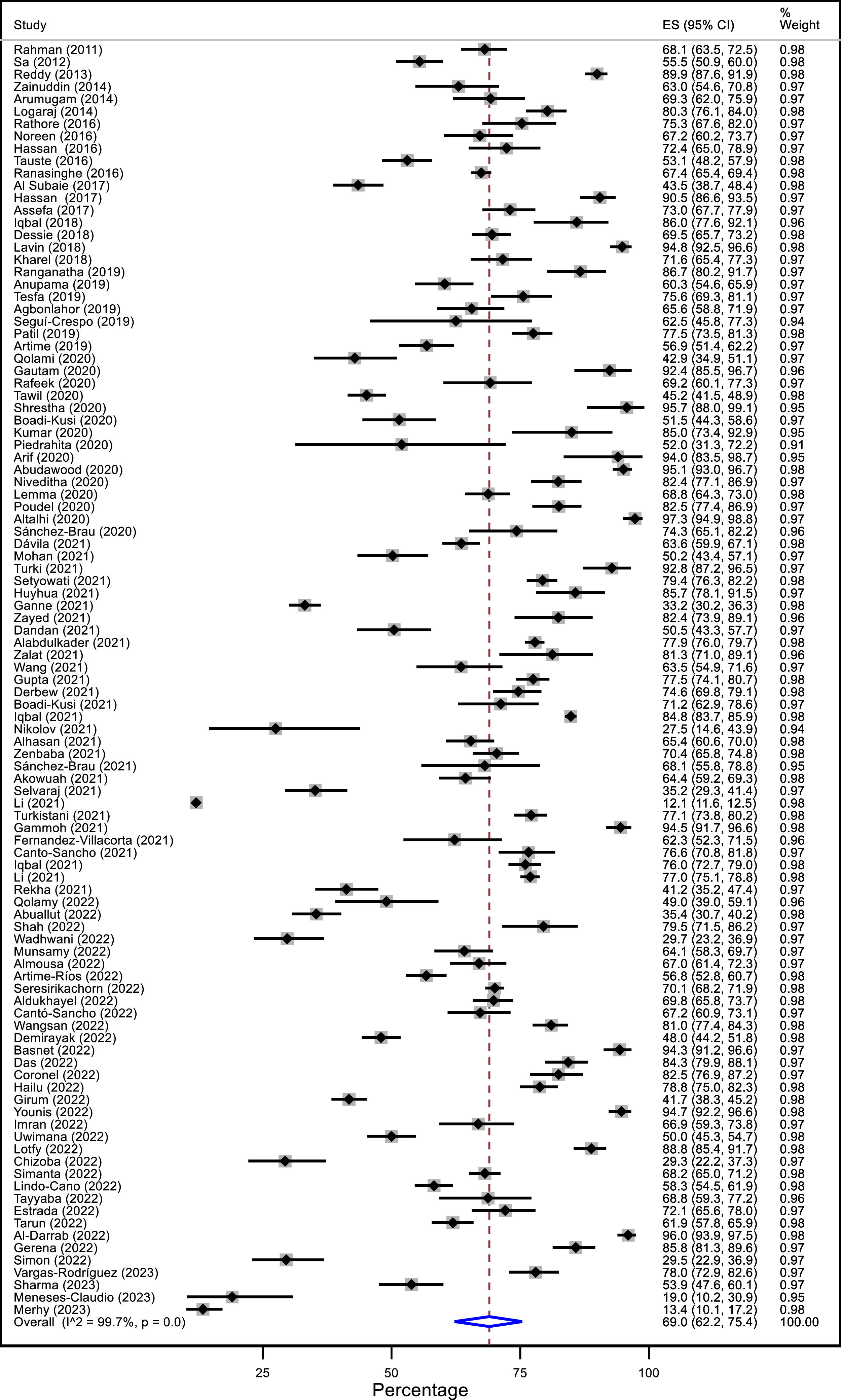

When meta-analyzing the studies, the prevalence of CVS was 69.0% (95% CI: 62.2 to 75.4; I2: 99.7%), with a range between 12.1 to 97.3% across studies (Fig. 3). This result presented a high heterogeneity. In addition, the prevalence was evaluated according to sex, continent, country income, diagnostic criteria, type of population, studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, the inclusion of patients with ophthalmological diseases, and level of risk of bias (Table 2). The point prevalence of CVS was higher in women than in men (71.4 Vs 61.8%). Among the four continents evaluated, Africa (71.2%) and Asia (69.9%) presented a higher prevalence than Latin America (66.6%) and Europe (60.9%). The studies that used the CVS-Q as diagnostic criteria had a lower prevalence (61.3%) than studies that used other criteria (75.4%). Regarding the type of population, the prevalence was lower in children and adolescents (50.5%) and higher in university students (76.1%). Studies conducted during the pandemic revealed a lower prevalence of CVS (64.6%). In addition, the prevalence was higher among contact lens wearers (73.1%). Despite these differences in point estimates, most results were imprecise, with overlapping confidence intervals between subgroups. Prevalence among country income subgroups, the inclusion of patients with ophthalmological diseases, and the risk of bias was similar (supplementary material 5).

Sensitivity analysisA sensitivity analysis was performed considering only those studies with adequate samples (N > 384). The prevalence was found to be similar between studies with adequate (67.6%) and inadequate (70.0%) sample sizes.

Publication biasOn inspection of the funnel plot, asymmetry was found, with fewer studies to the left of the estimate. This finding was corroborated by the significance of Egger's test (p < 0.001). In addition, an additional sensitivity analysis was performed by eliminating the study by Li et al. (a),7 which showed a low prevalence of CVS with a sample of 21 966 participants. In doing so, the funnel plot became more symmetric, and Egger's test was non-significant (p = 0.122) (see supplementary material 6).

Meta-regressionFor meta-regression analysis, three models were ran: 1) including all variables except mean VDTs hours of use and% of patients with contact lenses (72 studies), 2) including all variables except% of patients with contact lenses (27 studies) and 3) including all variables except mean VDTs hours of use (23 studies). In model 1, use of the CVS-Q scale was associated with a lower prevalence of CVS (β: −0.158; 95% CI: −0.289 to −0.028; p = 0.019). No other variable was associated with CVS prevalence. The overall models explained little of the residual heterogeneity (residual I2: model 1: 95.8%, model 2: 89.9%, model 3: 86.5%) and the variability between studies (adjusted R2: model 1: 14.3%, model 2: 32.8%, model 3: −38.1%) (see supplementary material 7).

DiscussionIn the present systematic review, the overall prevalence of CVS was evaluated. A total of 103 studies with a total of 66 577participants were included. Most studies were in Asia and workers or university students. In general, seven out of ten people presented CVS but with heterogeneous results across studies. Point prevalence was higher in women, university students, in Asian and African populations, in studies that did not use a validated instrument,in studies that were not realized during the COVID-19 pandemic, and in contact lens wearers. In meta-regression using a validated instrument was associated with CVS prevalence.

A systematic review with a search date of november 2021119 found that the prevalence of CVS in Ethiopia (Africa) was 73.2% (95% CI: 70.3 to 76.1). This result is similar to the meta-analysis of our study, as generally estimated, and by the Africa region subgroup, with 71.2% CVS prevalence (95% CI: 64.0 to 77.8). However, our overall results had a very heterogeneous prevalence, varying from 12.1 to 97.3%; it may be due to the different populations considered as not all are exposed to the same risk factors for CVS as personal, environmental, and ergonomic factors during the VDTs usage.120 In addition, the eligibility criteria for participants varied considerably.

Regarding the definition of CVS, it was observed that most studies used a wide variety of symptoms, and it is not clear which symptoms to consider to define this syndrome and how many symptoms at least would be necessary. One of the first reviews in the area121 categorized symptoms into groups: asthenopic, ocular surface related, visuals, extra-ocular, and transient blindness. Most of these symptoms were used as diagnostic criteria in the studies included in our review. It should be noted that in the meta-analysis carried out by Adane et al.,119 the top three symptoms reported by participants with CVS were blurred vision (34.3%), eye fatigue (32.1%), and watery eyes (30.6%). The only validated scale we found to measure this condition was the CVS-Q, which reported a lower prevalence in the subgroup and meta-regression analyses. The criteria to define CVS are not clarified in the literature, and having a standardized one is essential to propose future treatments.13,79,122–124 Furthermore, it is important to mention that some authors argue that subjective questionnaires without an ophthalmic exam are not ideal for documenting the true prevalence of CVS.39 In the review, we only identified one study that included evaluation by an ophthalmologist as a criterion.39

Regarding the prevalence by sex, we found that CVS was more frequent in females, similar to the reported in most previous studies of CVS. The latter was founded in other similar ocular pathologies in VDT users as dry eye disease121,125,126 and ergonomics-related problems such as musculoskeletal disorders.127 It could be because women are more likely to use VDTs than men in some populations,97 and the conditions of use, such as ergonomics, are also often different for men and women.128

Regarding the type of population, a higher prevalence of CVS was found in university students (76.1%). A review published in 2020129 on sedentary lifestyle in university students found that 72.9% of 2574 participants were in front of the screen (computer, television, and video games) for at least 2 h a day. Additionally, the computer and television were the most used VDTs, possibly representing a risk factor that would increase the prevalence in this population.129 Regarding workers, a CVS prevalence of 69.2% was found. A previous systematic review found that the prevalence was higher in bank-working personnel (73.8%).119 However, in the present research was not possible to establish a subgroup related to the work type, so the estimates for the different professions could be different.

The COVID-19 pandemic led millions of students and workers to continue their activities virtually, thus considerably increasing their exposure to VDTs.130 In this context, studies carried out during the pandemic are expected to present a higher prevalence of CVS. However, in the present review, a paradoxical finding was found since the prevalence was lower in the studies carried out during the pandemic. It could be due to the fact that while the time of VDT use increased, the conditions of its use during the lockdown were different. For example, in the case of workers, the lack of breaks in an office environment compared to devices usage at home during confinement and office ergonomics could also be involved.131 Nevertheless, there is no clear explanation for this finding.

Finally, a higher prevalence of CVS was observed in contact lens wearers.60 The presence of a contact lens on the ocular surface can cause tear alterations and can even cause discomfort in the adjacent areas such as the cornea, conjunctiva, and eyelids.60 This can vary depending on the material of the lenses and the conditions in which they are used such in wearers of conventional hydrogel and silicone hydrogel contact lenses.60 Therefore, it is recommended that contact lens wearers be considered as a risk group for developing CVS, and that they should be provided with a more exhaustive follow-up of their visual health.

The included studies have several limitations since the populations are heterogeneous since were considered various eligibility criteria, age groups, and occupations. Most studies were performed in Asia and Africa, so likely our results cannot be extrapolated to other populations. The high heterogeneity in the symptoms and criteria for defining CVS was also a limitation since most studies did not use a validated instrument. Other studies had different cut-off points, regardless of utilizing the same measurement instrument. Lastly, because some studies did not use appropriate sampling techniques or adequate sample size, so the internal validity of their results is questionable.

The present systematic review shows that the prevalence of CVS is high overall. In addition, some populations were identified that may have a higher prevalence. The relevance of these findings is that this trouble can cause a reduction in work/study productivity while reducing the computer user's quality of life.61 Thus, there is a need to investigate treatments and measures for this syndrome. However, a recent systematic review did not find high certainty evidence regarding some actions proposed as blue light filtering glasses and nutritional supplements to treat CVS-related symptoms.122 Besides, studies are needed to see the effectiveness of other proposed measures such as artificial tears, ergonomic optimization, adequate lighting, and frequent breaks to reduce CVS.121 It is relevant because, in the current context, the increased use of VDTs in people's lives and work will be inevitable.132 Given the low certainty of evidence on treatments, prevention becomes more important, emphasizing risk factors and promoting health in the most affected groups like university students or women. In this sense, it has been noticed that more knowledge of ergonomic practices and improving ergonomic conditions during VDT use are associated with a lower CVS prevalence.61

It is recommended that future studies employ validated scales to measure CVS. Also, it is recommended to use random sampling with a detailed description of the population (age, sex, type of population) and variables associated with CVS symptoms such as duration of VDT use, devices studied (computers, smartphones, others), or ergonomic and environmental factors. In addition, it is recommended to conduct further studies in regions such as America and Europe.

This systematic review has the following limitations: no search was done for studies in grey literature and could have excluded studies from some regions or specific populations. In addition, other factors that could explain the heterogeneity were not measured. Likewise, subgroup results should be interpreted with caution, as they are generally imprecise. However, the strengths of this review are that an exhaustive search in several databases was elaborated, and the references of the included studies were reviewed, finding a significant number of investigations. In addition, a large sample size was obtained, and subgroup and meta-regression analyses were performed to explore heterogeneity sources. Although, the high heterogeneity could not be explained by the variables proposed.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the prevalence of CVS overall was 69.0%, Point prevalences show that women, university students, populations from Asia and Africa may be more affected by this syndrome, and contact lens wearers. Point prevalence was also higher in studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic and that did not use a validated instrument. Preventive strategies and interventions to decrease the prevalence of this syndrome are recommendable, especially in the most affected populations. More studies using validated scales are needed to standardize the definition of CVS.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.