This study aims to determine the overall prevalence of ocular conditions in a population from 19 to 64 years old, presenting with refractive-based symptoms only. Results could impact clinical standard of eye care on a similar population.

MethodsThis is a retrospective study on patients seen for an eye examination at the Clinique Universitaire de la Vision (CUV), between January 2007 and 2009. Files of individuals who presented with refractive symptoms were only selected and classified by file number. Then, every third file from the beginning was kept and reviewed by a reader. A second reader did the same with every third file from the end. Both readers were trained to use the same analysis grid to classify the diagnosed ocular conditions. In the case of multiple findings, the most severe condition was considered. The overall prevalence of ocular conditions was determined by calculating their occurrence divided by the number of files analyzed.

ResultsA total of 860 charts were analyzed. In 26.1% of the cases an ocular condition was diagnosed. This work establishes a higher prevalence of ocular conditions compared to another study conducted in Canada in the past. This difference can be explained by a different analytical methodology and by the fact that all examinations, in this study, were made under pupillary dilation.

ConclusionThe presence of ocular conditions in 26% of asymptomatic patients supports the need to assess ocular health under pupil dilation as part of any eye examination. However, further cost-to-benefit analysis is required before establishing such a recommendation.

Este estudio trata de determinar la prevalencia general de las condiciones patológicas oculares en una población de pacientes de 19 a 64 años de edad, que presentaron únicamente síntomas refractivos. Los resultados podrían suponer un impacto para los estándares clínicos de cuidado ocular en poblaciones similares.

MétodosEste es un estudio retrospectivo sobre pacientes examinados en la Clinique Universitaire de la Vision (CUV), entre Enero de 2007 y 2009. Se seleccionaron y clasificaron por número de archivo aquellas historias de pacientes con síntomas refractivos únicamente. A continuación se seleccionó cada tercer archivo contando desde el inicio, el cual fue revisado por un mismo lector. Un segundo lector realizó la misma operación con cada tercer archivo contado desde el final. Ambos lectores fueron formados para utilizar la misma cuadrícula analítica para clasificar las condiciones oculares diagnosticadas. En caso de múltiples hallazgos se consideró la situación más severa. Se determinó la prevalencia general de las condiciones oculares mediante el cálculo de su ocurrencia, dividida por el número de archivos analizados.

ResultadosSe analizó un total de 860 historias. En el 26,1% de los casos se diagnosticó una condición patológica ocular. Este trabajo establece una mayor prevalencia de las condiciones patológicas oculares en comparación a otro estudio realizado en Canadá en el pasado. Esta diferencia puede explicarse por el uso de una metodología analítica diferente y por el hecho de que todos los exámenes de este estudio se realizaron en condiciones de dilatación de la pupila.

ConclusiónLa presencia de condiciones patológicas oculares en el 26% de los pacientes asintomáticos apoya la necesidad de evaluar la salud ocular como parte de cualquier examen ocular. Sin embargo, se hace necesario un análisis adicional coste-beneficio antes de establecer dicha recomendación.

The prevalence of common specific diseases and disorders is well known,1 at least in developed countries where public health data are collected. First, this knowledge may help practitioners to consider who is at risk among their patients and to better diagnose any pathological condition.2 For example, patients over 50 years old are routinely screened for glaucoma on this basis. Second, it helps politicians and bureaucrats to shape public health policies and to estimate for the cost associated with the management of specific diseases. Third, prevalence analysis can help universities and colleges to plan the number of human resources to train. Fourth, in some cases, a higher prevalence of a specific disease can encourage healthcare system administrators to put a better screening program in place, or to adopt a new treatment strategy, to reduce morbidity and disease-associated costs.3 Systematic screening programs for diabetic eye disease have been developed in many countries and represent a good example of such policies. They can also help to plan targeted educational campaigns to raise public awareness in order to modify their behavior.4 For example, large-scale surveys in the U.S. have shown that only 11% of people are aware that diabetic retinopathy comes with no initial warning symptoms and as little as 8% for open angle glaucoma.5 Similarly, clinical research on rhegmatogenous retinal detachments has shown that approximately 1 patient out of 3 (31.3%) has at least one asymptomatic retinal finding predisposing to retinal detachment.6 In such cases, educating patients at risk may prompt early detection, which helps limit the costs and negative impact of the disease.

To this point, a recent study7 proved that a substantial burden results from vision loss and eye disorders in the U.S. Estimates for the population younger than 40 years of age are $14.5 billion US in direct costs and $12.2 billion US in lost productivity. In addition, vision loss costs society 215,000 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). This adds another $10.8 billion US, bringing the total cost of vision loss and eye disorders to $37.5 billion US$ or $17,400 US per patient.

On the other hand, some health policies are apparently not defined on the basis of cost-effectiveness analysis. For example, in 2010 British Colombia (BC) became the first and still the only jurisdiction in North America to deregulate its optical market in response to the industry's lobbying efforts, with no evidence of any public health benefit. This decision was supposedly made to lower the cost of goods, but without evaluating the potential impact of such a decision on eye health. Since then, individuals aged 19–64 years old can purchase their glasses and contact lenses based on electronic refraction data (sight testing) gathered by any lay person selling ophthalmic lenses, not validated as a prescription by an eye care professional. This deregulation implies that, in this jurisdiction, a complete eye exam, including ocular disease screening, is no longer required to obtain new glasses or contact lenses.

It is hard to estimate the immediate and long term impact of this decision because, contrary to confirmed ocular pathology, there is very limited data available about the prevalence of missed pathologies among a population consulting for sight testing, with no symptoms other than those refractive in nature.

However, we can estimate that this prevalence increases with time and aging of the population. In fact, it is known that significant fundus findings in patients presenting with no symptoms increase with age.8 On the other hand, there is no strong evidence that dilated fundus examinations, systematically performed, in asymptomatic younger patients yield a high level of pathology findings.9 This is the reason why the recommended eye examination schedule becomes more frequent for older people, although no one knows the actual prevalence of ocular abnormalities in asymptomatic patients.

Consequently, this study aims to establish the prevalence of ocular conditions affecting asymptomatic individuals for a cohort including younger and older patients between 19 and 64 years of age, seeking for an eye exam solely based on refractive symptoms. The second aim is to categorize and establish the prevalence of each ocular condition diagnosed in the course of their eye examination. These elements are important because they could impact clinical standards of eye care for similar populations.

Materials and methodsThis is a retrospective study. It was conducted after obtaining Institutional Review Board approval (Comité d’éthique de la recherche en sciences de la santé – CERSS – Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec). The CUV electronic database files of individuals between 19 and 64 years of age at the time of their last comprehensive eye exam, between January 2007 and January 2010, were selected. Files of individuals with a positive case history containing previous knowledge of ocular pathology or the presence of symptoms suggesting an ocular condition were excluded. For example, people known to have cataracts or reporting recent occurrences of flashes and/or floaters were excluded. However, it is possible for a patient to present with refractive symptoms and have pathological conditions, such as a cataract inducing myopia increase, unbeknownst to patient, students or supervisor. These cases were obviously included because their symptoms are related to refraction and not to an alarming sign of an ocular pathology. This study aims to identify them. With the same rationale, files of patient with high myopia, which are at a higher risk to present peripheral conditions, were not kept if the patient mentioned this risk as the reason to consult. On the other hand, file of a high myopic patient was kept for analysis if the patient was asymptomatic and not knowledgeable about existing retinal conditions, and if the eye examination was initiated on the basis of refractive symptom only. Contact lens wearers were considered only if they were asymptomatic at the time of their visit, and with no proven record of anterior segment diseases in the past.

As suggested by the public health department experts at Université de Montréal, study candidates were selected by keeping every third file from the beginning and the end of a list, containing the total number of files selected. They were then retrieved and split between two readers trained to use the same analysis grid.

File analysis is simplified by the fact that the CUV policy manual sets standards for case histories and eye examinations. Examinations were performed by optometry students (4th year) under the supervision of certified optometrists, responsible for establishing the diagnosis and the treatment plan. Clinicians and students had to follow the procedures and guidelines as written. The examination file was consequently standardized for every visit made.

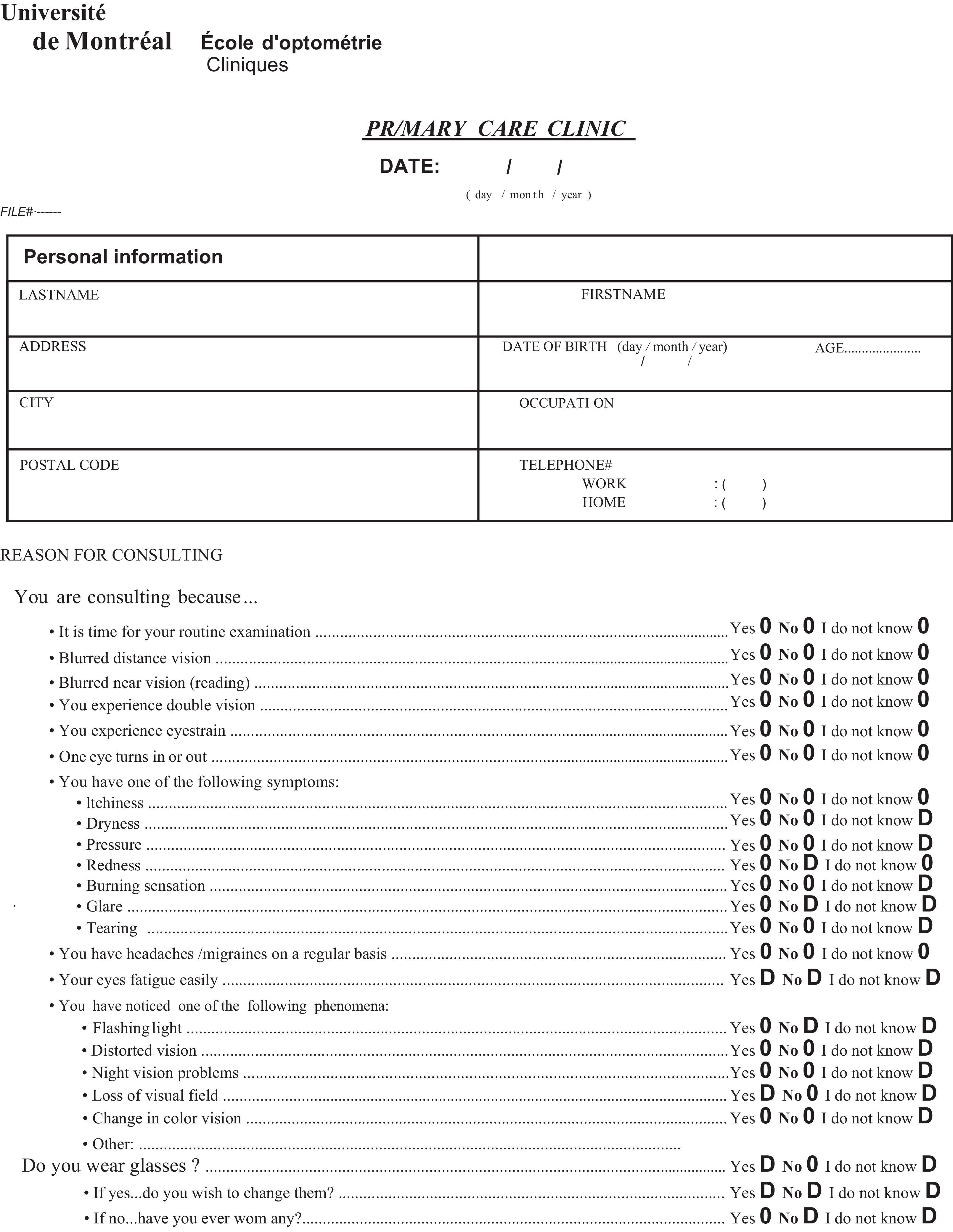

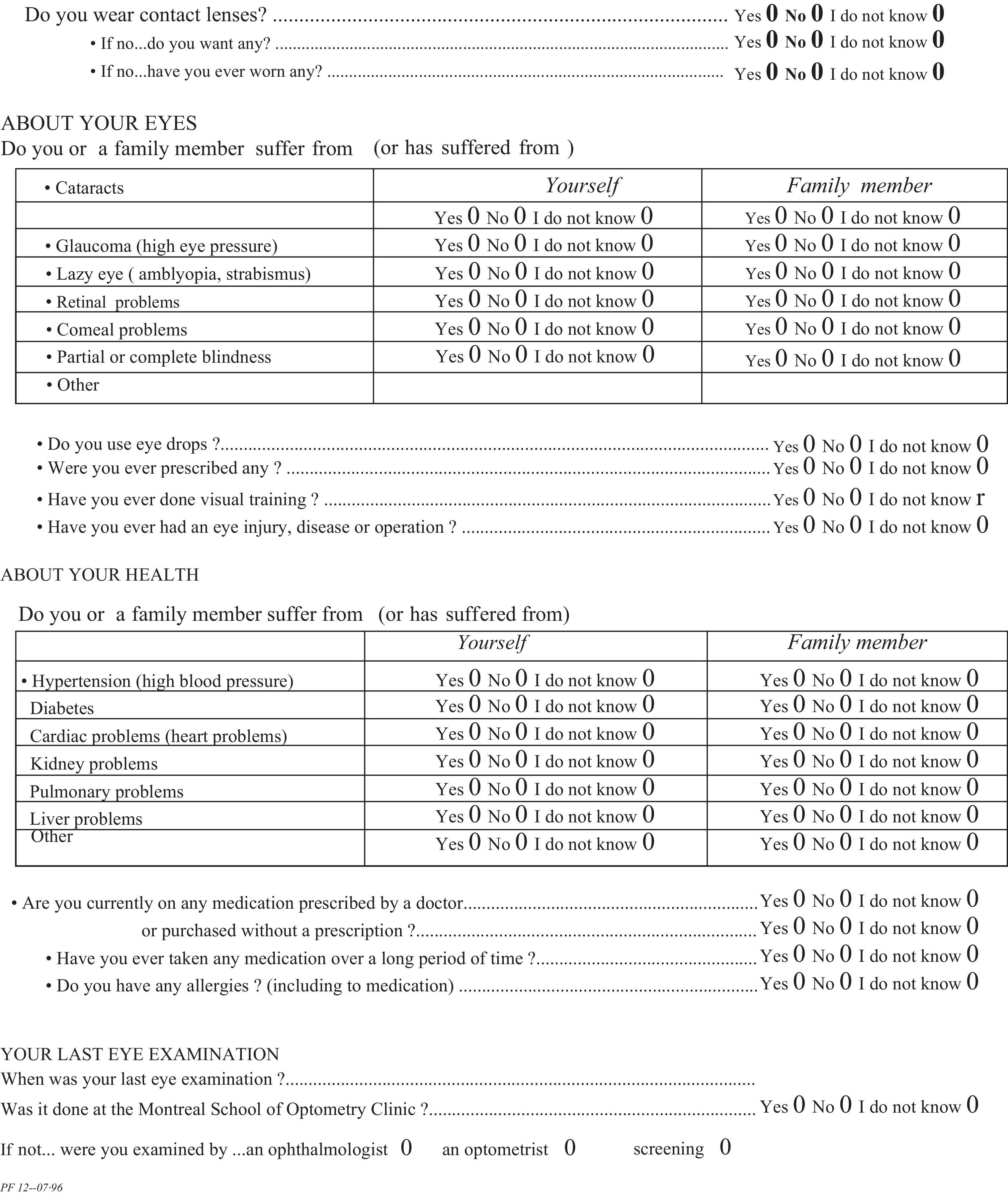

The first step was to revise the selected files and make sure that subjects were asymptomatic of any ocular conditions, based on their case history, except for refractive symptoms. This included a careful analysis of the pre-exam questionnaire filled in by the patient at the time of consultation (see appendix). Once the case was evaluated as asymptomatic, the second step was to identify the presence of an ocular condition, on the basis of the written diagnosis, and/or the recommendations made to the patient as recorded and/or any action taken following the examination (treatment prescribed, follow-up planned or referral made). For example, if macular drusen or a variation in macular pigmentation was noted in the file, the condition would be only considered macular degeneration if the term appeared in the diagnosis box and/or if the patient education was done, including risk factor identification and written recommendations (vitamins supplements, smoking cessation, Amsler grid, etc.). The same rationale was applied for peripheral retinal findings: a tuft or lattice degeneration was only considered as an ocular condition following patient education on symptoms of retinal detachment and/or if a further fundus exam under dilation was planned to control evolution of the condition. The presence of a cataract not previously known to the patient was also considered an ocular condition, on the understanding that it could trigger the causative symptoms (refractive-based) for seeking out an eye examination.

A list containing all conditions that can be screened during a routine eye exam was provided to both reviewers. Once identified, the condition was graded (low-moderate-severe). Only one condition per file (the most severe) was kept for further analysis. For example, if a patient showed low signs of ocular dryness (without symptoms) and moderate signs of dry macular degeneration, the latter was kept. In case of any doubt, the first reviewer would ask the second to revise the chart for classification purposes. Both had to agree on the presence of the same ocular condition and its severity in order to retain the file for analysis. Lastly, the sum of each ocular condition was calculated. It was then easy to determine its prevalence based on the total number of files analyzed.

StatisticsMeans and standard deviations were calculated for demographic data. The prevalence of patients for whom at least one asymptomatic condition was found was calculated and compared to the only study10 published for a Canadian population using the Chi-squared method (χ2).

ResultsA total of 2548 files were extracted from the database, representing all of the individuals seen for a comprehensive eye examination between 2007 and 2009. From this number, 115 files were rejected because of incomplete data. Based on the suggested procedure, a total of 846/2,433 (34.7%) files were then processed. This cohort was composed of 389 men and 497 women, mostly Caucasian (69.2%), aged 41.7 (±8.9) years. A majority of these patients (73.7%) were myopes with a mean refractive error of −3.65 (±2.27D), including 56% showing a low level of astigmatism (−0.87±0.42D). The characteristics of this cohort are comparable to the presenting population of the clinic.

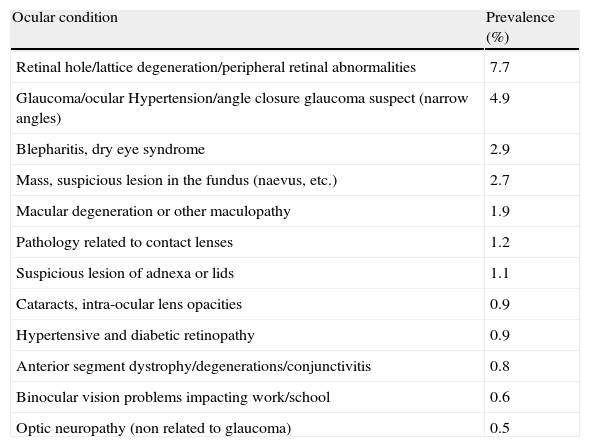

In all, 220 individuals presented at least one asymptomatic ocular condition (26.1% of the files analyzed). Retinal conditions were the most common (13.7%), followed by glaucoma/ocular hypertension (4.9%), dry eye (2.9%) and anterior segment diseases (3.1%). The prevalence of asymptomatic conditions is detailed in Table 1.

List of ocular conditions as found during routine eye examination on asymptomatic patients.

| Ocular condition | Prevalence (%) |

| Retinal hole/lattice degeneration/peripheral retinal abnormalities | 7.7 |

| Glaucoma/ocular Hypertension/angle closure glaucoma suspect (narrow angles) | 4.9 |

| Blepharitis, dry eye syndrome | 2.9 |

| Mass, suspicious lesion in the fundus (naevus, etc.) | 2.7 |

| Macular degeneration or other maculopathy | 1.9 |

| Pathology related to contact lenses | 1.2 |

| Suspicious lesion of adnexa or lids | 1.1 |

| Cataracts, intra-ocular lens opacities | 0.9 |

| Hypertensive and diabetic retinopathy | 0.9 |

| Anterior segment dystrophy/degenerations/conjunctivitis | 0.8 |

| Binocular vision problems impacting work/school | 0.6 |

| Optic neuropathy (non related to glaucoma) | 0.5 |

In order to interpret our results, we would underscore that the definition of asymptomatic conditions can differ from one study to another and, consequently, results can be difficult to compare. Contrary to our approach in this study, it could be argued that refractive error change, per se, can be considered a symptom/sign of certain ocular condition, and some authors may exclude subjects based on this argument. For example, cataracts will develop with an increase in myopia. Although we know this is true, if the patient is unaware of the condition, the consultation can be considered that concerns only refractive reasons. We aimed to identify pathology or ocular conditions in patients asking for a vision test or attending to change their glasses and ignoring that they have an ocular health problem. We believe that our approach will help identify the risk of missing a pathology during patient sight testing. On the other hand, our study does not include patients who are totally asymptomatic (no symptoms at all, we consider the refractive symptoms) because they are rarely seen on a routine basis in an optometry clinic. Our population was composed of individuals consulting on their refractive needs only, and our results should be interpreted accordingly. Because of the nature of the ocular conditions found, we believe that our results can be applied elsewhere, with a similar population.

According to these findings, one out of four patients presenting with an ocular condition not known to him/her merits immediate treatment, follow-up or a referral to another health care practitioner. This prevalence is higher if compared to the results of another study10 made in Canada in 2003 where the author found that ocular disease was present in 14.4% of the patients. With respect to this study, the total prevalence of asymptomatic ocular conditions found in our series is statistically higher (26.1% vs. 14.4%; p=0.0025). In another study, other authors found an overall prevalence of undetected eye disease of 16.67%11 in a different population.

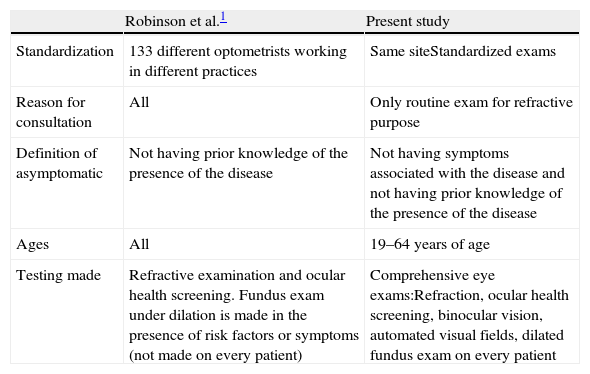

Several elements can explain the deviations from the other Canadian study (see Table 2). First of all, the population studied was, in that case, younger than ours. In general, the prevalence of ocular conditions increases with age. Second, the time spent on performing an eye examination is longer in a university setting (average of 2h/patient vs. 30min/patient), thus allowing for more extensive testing of the patient. From that perspective, the most important factor is certainly that fundus evaluation is made under pupil dilation, using fundus lenses with binocular indirect ophthalmoscope and slit lamp. This testing was done on every patient, as it is the policy for every patient consulting at U. de Montréal, which was not the case in the other study. At that time, more than 10 years ago, routine dilation was not used as a regular practice in optometric offices in Canada, as it is today. An increased amount of ocular findings in the peripheral retina, such as lattice degeneration, retinal holes, vitreo-retinal tufts and choroidal naevi requiring follow-up is certainly to be expected when dilation becomes a standard care practice. If the fundus assessment is made without dilation, peripheral retinal conditions can be easily missed. In one study, the authors proved that of 32 posterior pole anomalies that required action, 38% were missed during the natural pupil examination. Moreover, more than half of abnormal conditions not requiring immediate action were also missed.12 One other author6 rated the prevalence of peripheral retinal conditions needing close follow-up or referral to an ophthalmologist at 8%, consistent with the findings of the present study (7.74%). In both studies, dilation was performed with every patient, which was not the case for Robinson et al., who estimated this prevalence at only 1.35%. The overall difference between our ocular findings and those of Robinson can be largely explained by the fact that peripheral retinal problems remained occulted in the latter.

Differences between the present study and the Robinson et al. study.

| Robinson et al.1 | Present study | |

| Standardization | 133 different optometrists working in different practices | Same siteStandardized exams |

| Reason for consultation | All | Only routine exam for refractive purpose |

| Definition of asymptomatic | Not having prior knowledge of the presence of the disease | Not having symptoms associated with the disease and not having prior knowledge of the presence of the disease |

| Ages | All | 19–64 years of age |

| Testing made | Refractive examination and ocular health screening. Fundus exam under dilation is made in the presence of risk factors or symptoms (not made on every patient) | Comprehensive eye exams:Refraction, ocular health screening, binocular vision, automated visual fields, dilated fundus exam on every patient |

Third, examination was made by an optometry student (4th year) but controlled and checked by an experienced optometrist. This duplication in testing lowers the risks of missing an ocular condition. Finally, the other study was based on a multi-analysis of files gathered at 133 sites, each with its own rules and practices. In our case, all of the exams were conducted and recorded under the same practice guidelines and with the same file template, leading to a more standardized procedure. Unfortunately, readers did not identify the number of different clinicians and students involved in the process. Because students and clinicians adhere to the same standards, we do not believe that this represents a significant factor likely to alter our conclusions.

These results could impact the clinical standards of eye care in Canada and elsewhere. Specifically, based on our findings, the current practice in British Columbia or in other jurisdictions around the world, where non-professionally trained individuals could prescribe glasses and contact lenses, may lead to the non-diagnosis of significant ocular pathologies that are vision and sight threatening. Comprehensive eye exams, including ocular health assessments, remain one of the practitioner's most important tools in preventing disease.13 Optometrists can play a key role in any public health system by offering opportunistic detection of ocular disease in asymptomatic patients consulting for refractive problems.14

Our data highlight the importance of incorporating dilated fundus examination as a routine procedure during eye examinations of asymptomatic patients, despite rare but existing consequences, such as ocular irritation, allergy to the drugs used to dilate the pupil, the potential to induce angle-closure glaucoma and the transient effect of the procedure on the patient's vision. As shown, a dilated fundus assessment could lead to early detection of ocular conditions and, eventually, help reduce morbidity and the costs associated with eye diseases. Consequently, it would not be considered good practice to conduct a sight testing without assessing ocular health at the same time. This could leave the patient at risk of eye diseases.

Does that mean that every single asymptomatic patient should be assessed for ocular disease? Obviously, the answer is yes, although the frequency of such exams has yet to be determined. Some evidence shows that clinically significant ocular conditions increase with age.15 For that reason, optometric and ophthalmology regulatory bodies recommend periodic eye examination, although there is no consensus on the optimal moment to assess patients.

Part of the problem is that this type of recommendation/regulation should be analyzed through a cost-benefit ratio approach. Health agencies and politicians must consider these factors before adopting or modifying regulations and policies related to eye care and the optical market, to establish recommendations concerning the optimal schedule for comprehensive eye examinations, and to determine the appropriate coverage of professional services by public funding.

Based on the fact that vision loss and eye disorders can cost $17,500 US per patient, as already mentioned, and estimating the cost of a comprehensive exam at $100 US per patient, it is readily apparent that public health system coverage of a comprehensive eye examination is profitable. For example, take an individual 20 years old who is seen by an optometrist every 2 years up to the age of 65 and every year thereafter, with a life expectancy of 85 years of age. This implies 42 eye exams throughout his life for a total coverage cost of $4200 US. Based on our findings, 26.1% of the population has an ocular condition or an eye disorder that could potentially lead to a vision impairment or loss. This means that for every four patients we see, we will detect and screen one problematic case. The total cost of such a screening (4×$4200 US) is still less than the cost of a single case of an eye disorder ($17,500 US). However, this evaluation is only valid if we admit that early detection always prevents the development of a vision loss.

ConclusionIn conclusion, about 1 in 4 patients (26.1%) between the ages of 19 and 64, consulting with refractive-based symptoms only, present with at least one asymptomatic ocular condition that requires treatment, referral to another health professional, careful follow-up or patient education. This underscores the importance of assessing ocular health, ideally under pupil dilation, at the same time that the refractive examination is performed.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors thank Sara Lahoud and Rafael Elalouf for their help in gathering the data presented in this paper.