Patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy can be very challenging to manage secondary to the complex nature of their disease presentation. Patients may present with a variety of ocular findings including: lid retraction, periorbital and lid swelling, chemosis, conjunctival hyperemia, proptosis, optic neuropathy, restrictive myopathy, exposure keratopathy and/or keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Mini-scleral and scleral lens designs have been important in the management of irregular and regular corneas, and in the therapy of ocular surface diseases.

We present here the case of a 48-year-old Caucasian male who had been diagnosed with Graves’ ophthalmopathy 13 years earlier. With significant ocular surface staining and over ten diopters of astigmatism, the patient had never been able to wear contact lenses comfortably. After being fit with the Mini-Scleral Design™ lenses, his vision improved to 20/25 OU, his ocular surface improved, and overall quality of vision increased.

Puede ser difícil tratar a los pacientes con Oftalmopatía de Graves, debido a la naturaleza compleja de la presentación de su enfermedad. Los pacientes pueden presentar variedad de manifestaciones oculares tales como: retracción parpebral, hinchazón periorbital y parpebral, quemosis, hiperemia conjuntival, proptosis, neuropatía óptica, miopatía restrictiva, queratopatía por exposición y/o queratoconjuntivitis seca. Los diseños de lentes mini esclerales y esclerales han resultado ser importantes para el tratamiento de las córneas irregulares y regulares, y para la terapia de las enfermedades de la superficie ocular.

Presentamos el caso de un varón caucásico de cuarenta y ocho años al que se había diagnosticado Oftalmopatía de Graves trece años antes. Con una significativa tinción de la superficie ocular, y más de diez dioptrías de astigmatismo, el paciente no había podido llevar nunca lentes de contacto con comodidad. Tras adaptarle las lentes Mini-Scleral Design™, su visión pasó a ser de 20/25 OU, mejorando su superficie ocular e incrementando su calidad de visión general.

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder that is most commonly known as hyperthyroidism. This disease is defined by increased thyroid gland synthesis and production of the thyroid hormone.1 Manifestations of the disease are thought to be caused by production of antibodies that bind to the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) and therefore result in an overproduction of the T3 and T4 hormones.2 While patients with Graves’ disease often present with fatigue, weakness, heat intolerance, weight loss, tachycardia, and tremor, they may also present with ophthalmopathy; one of the main and potentially serious clinical features. Characteristic ocular findings include lid retraction, lid lag, proptosis, restrictive extraocular myopathy, optic neuropathy and inflammation of the ocular surface.2,3 Around 1/2000 women per year are affected by Graves’ and it occurs 5–10 times lower in men, with peak onset at 40–60 years of age.1 Approximately 60% of patients with Graves’ disease develop Graves’ ophthalmopathy and 85% of patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy present with ocular surface disease.2

Patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy will typically present with advanced ocular surface disruption which can lead to corneal complications and irregularities.4 Patients with these problems who also require refractive correction may experience difficulties in achieving both acceptable quality of vision and improvement in their ocular surface with traditional contact lens designs. Although smaller diameter lenses work well for many patients, they are somewhat limited in their tear reservoir capacity, whereas mini-scleral and ultimately scleral contact lenses can produce a much larger tear reservoir, reducing mechanical disruption to the ocular surface. When the cornea becomes more irregular, the fitting process becomes more complex. A scleral lens may be indicated for the irregular cornea to create a smoother refractive surface and to avoid pressure to the corneal apex, thus minimizing scarring. Even with maximum topical and systemic therapy, these patients’ ocular conditions may be difficult to manage. With the option of mini-scleral and scleral lens designs, patients now have an option to protect the cornea and offer better vision. Scleral contact lenses allow for successful and comfortable fitting and vision in patients with complex corneas. These lenses also serve as a pre-corneal fluid reservoir which provides optical correction while rehabilitating the ocular surface.5–7 The following case involves a patient with Graves’ disease, severe ocular surface disruption, and keratoconus. Secondary to his irregular astigmatism and ocular surface disease, the patient was fit with mini-scleral lenses not only to assist in the rehabilitation of his ocular surface, but also to improve the quality of his vision.

Case reportA 48-year-old Caucasian male initially presented with complaints of blur at distance and near with his current hybrid lenses, double vision at the end of the day, and significant redness and irritation that did not improve with traditional supportive dry eye therapy. The patient had been diagnosed with Graves’ 13 years earlier and was status-post a complete thyroidectomy. He was being monitored closely by his endocrinologist. The patient had failed with all other lens modalities and was concerned that the problems with his vision and ocular discomfort would interfere with his ability to continue working.

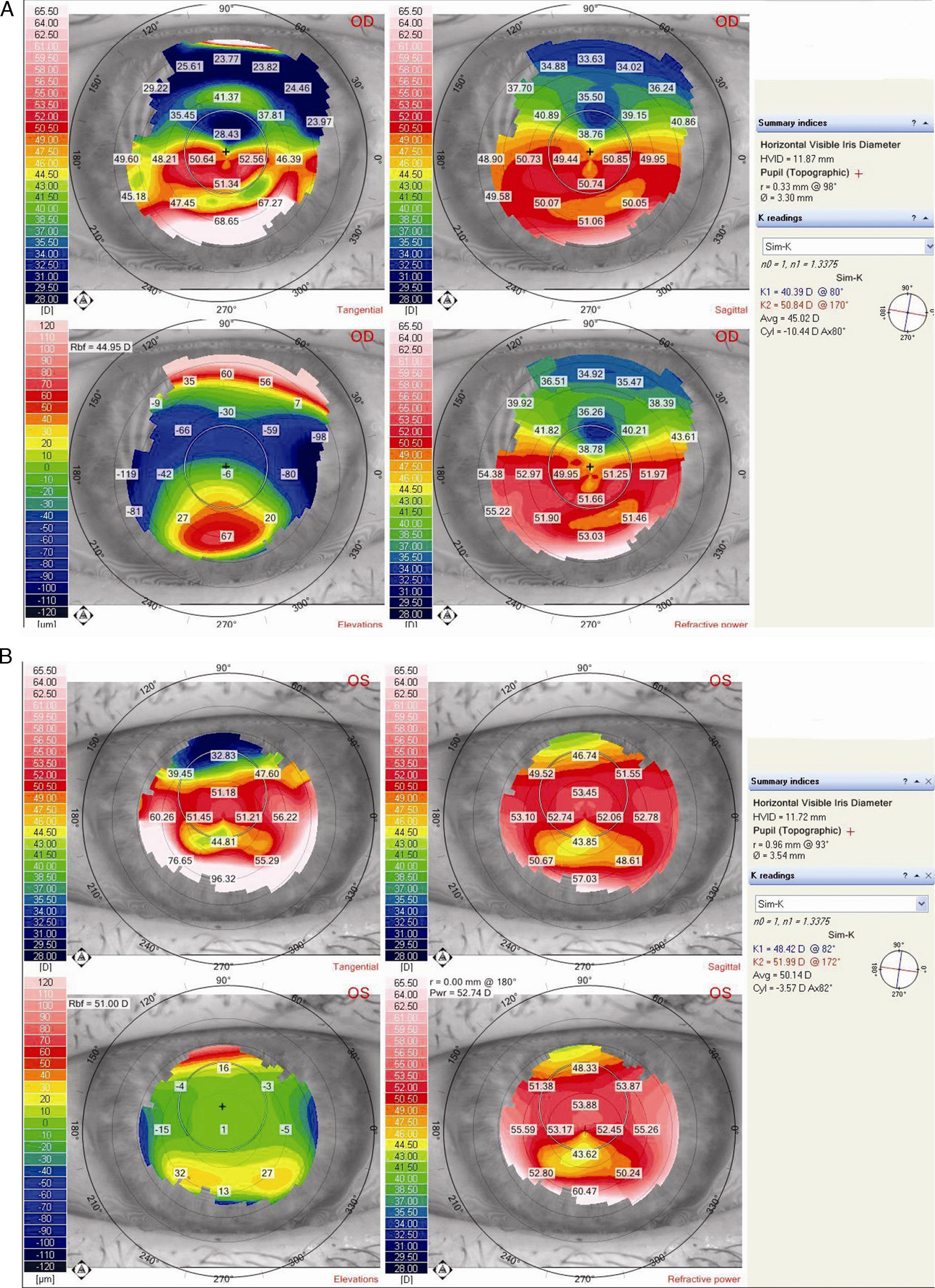

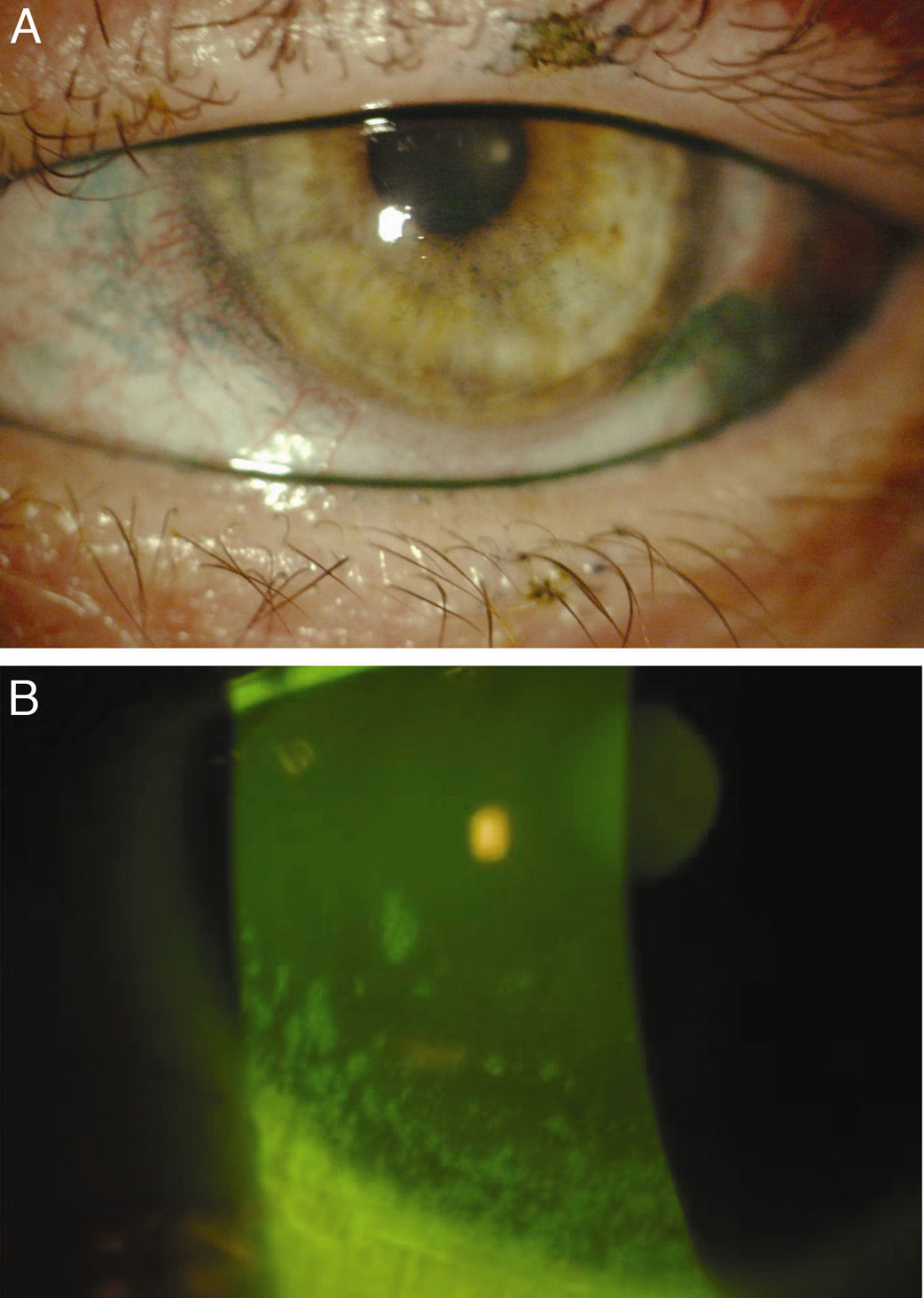

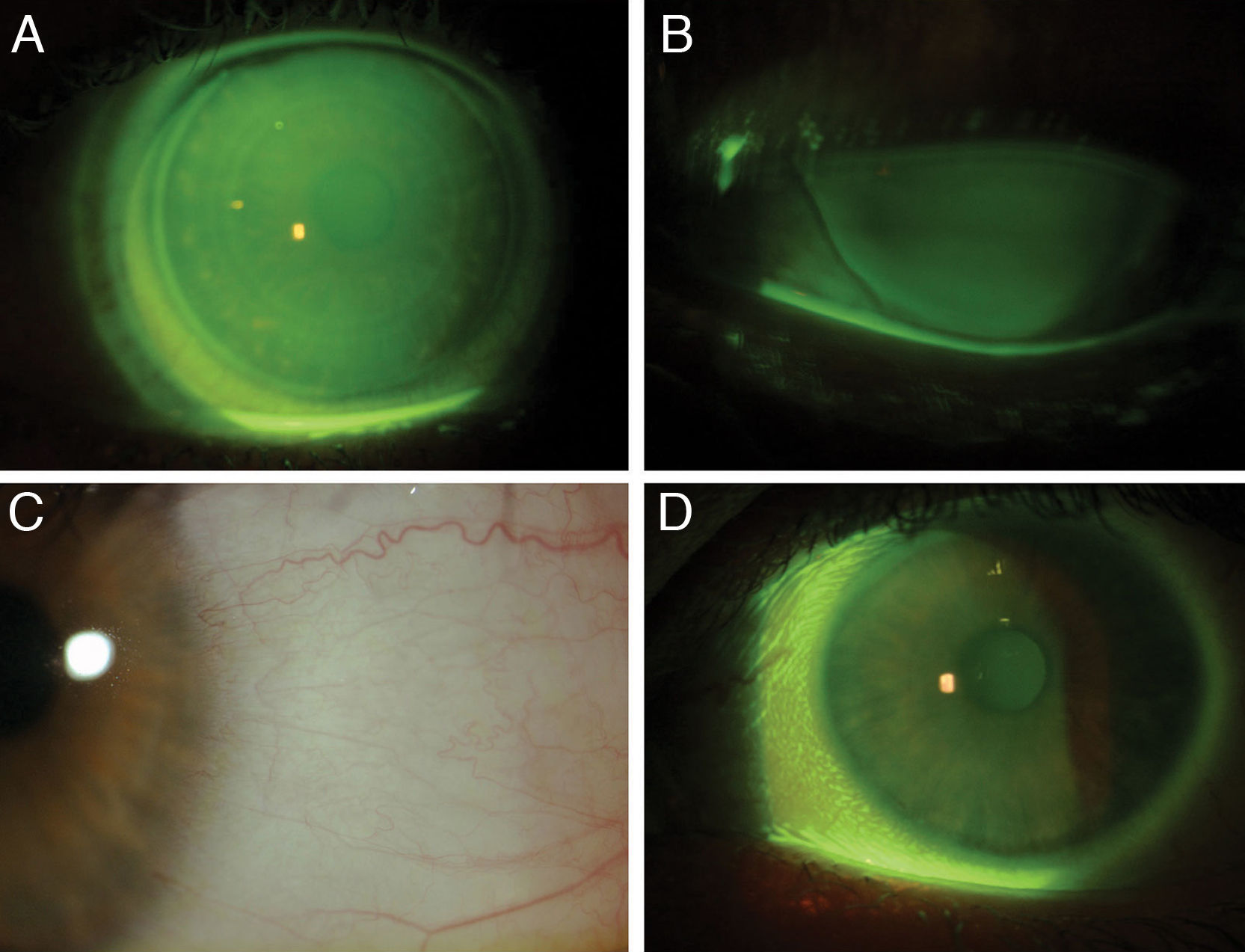

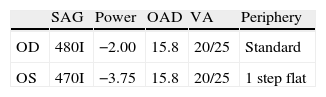

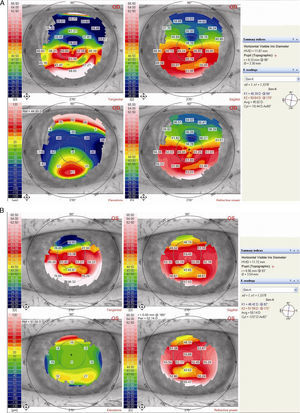

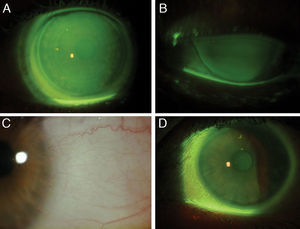

Entering corrected vision with his hybrid lenses was 20/30 OD and 20/50 OS. His refraction was −5.50−4.50×082, 20/80 OD and −11.00−3.00×115, 20/200 OS. Topographies showed irregular astigmatism that was greater in the right eye than the left, 10.44 diopters OD and 3.57 diopters OS (Fig. 1A and B). Topographies also revealed corneal ectasia (keratoconus) OU. Upon further investigation of the patient's ocular history, keratoconus had not been discussed with the patient in previous examinations. No evident restriction was noted upon extra-ocular motilities, even though the patient complained of slight diplopia at the end of the day. Mild proptosis was noted OU, with an increased vertical fissure width measured. Marginal Reflex Distance 1 was 6mm for both the right eye and left eye. Marginal Reflex Distance 2 was 7mm for the right eye and 8mm for the left eye. The corneas showed 2+ diffuse sodium fluorescein staining and the conjunctiva showed 3+ lissamine green staining (Fig. 2A and B). Schirmer scores without anesthetic were 13mm OD and 8mm OS. The patient was started on Restasis® (cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion) 0.05% BID, Lotemax® (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension) 0.5% BID, preservative free artificial tears QID, and preservative free ointment QHS OU to improve his ocular surface and increase tear production. Intraocular pressure was 12mmHg OD and 14mmHg OS by Goldmann applanation tonometry. Dilated fundus examination was unremarkable.

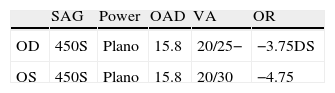

Successful use of scleral lenses in the management of ocular surface disease has been well documented.5–7 After reviewing the patient's initial presentation, we wanted to begin the lens fitting process with the 18.2mm Jupiter series to create increased surface coverage and enhance the therapeutic effect of the lenses. However, after lengthy discussion with the patient and the fact that the patient did not have insurance at the time of the initial contact lens fitting, mini-scleral lenses were selected to try to keep costs down while still having some therapeutic effect to the ocular surface. The 15.8mm Mini-Scleral Design™ lenses (Blanchard Contact Lenses Inc) were selected due to the patient's irregular astigmatism, ocular surface disruption, and discomfort with other lens modalities. Mini-scleral lenses were also chosen to provide a protective barrier between the lids and the cornea during blinking and to provide continuous corneal hydration with the tear reservoir, thus assisting in healing the corneal epithelium. Following the fitting guide, which is based on sagittal height instead of back surface radii, initial lenses were selected (Table 1). The initial lenses selected had a standard profile curve. Key endpoints to look for when assessing the lens fit are: central alignment to central clearance or vault, limbal vault, and conjunctival alignment with no impingement or blanching. These are important factors to look for so that the lens may create a corneal bathing effect. The lenses were ordered in Boston XO2 material (Dk 141) to allow for maximum oxygen transmission.

With this first pair of lenses, central touch was noted OD>OS, with excessive limbal clearance in the mid-peripheral zone, and slight scleral impingement after about 20min of settling. The left lens demonstrated more central vault with peripheral impingement. Although the first set of diagnostic lenses were not an ideal fit, the patient immediately noted improved ocular comfort, and a significant improvement in the quality of his vision. With the first pair of diagnostic lenses, the patient's vision improved to 20/25 OD and 20/30 OS.

The final lenses were ordered with an increased central vault OU. The periphery was adjusted to decrease conjunctival impingement OS (Table 2). With these adjustments, the profile curve was also adjusted to the Increased-I curve to provide adequate vault in the midperipheral-limbal clearance zone. The overall pattern demonstrated increased central clearance, adequate limbal clearance, and no conjunctival impingement in the periphery. The patient's comfort level increased, and the cornea had less staining (Fig. 3A–D). The patient was instructed to increase his wear time to six to eight hours of wear per day and was instructed on the proper use of Clear Care® Cleaning and Disinfection solution, a hydrogen peroxide-based solution. He was also instructed to fill the lenses with non-preserved saline prior to lens insertion. The patient's corneal staining improved from 2+ fluorescein staining to trace staining after 3 weeks of wearing the mini-scleral lenses. The patient has been successfully wearing the lenses for 5 months noting an increase in the clarity of his vision, quality of his vision, and an improvement in ocular comfort. The periphery of the final left lens has been modified again to decrease impingement and improve the overall fluorescein pattern.

Patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy may have severe ocular complications resulting in decreased vision and corneal deformities that are difficult to correct with glasses alone. While the exact etiology of ocular dryness due to Graves’ ophthalmopathy remains unclear, several studies have suggested that the increased orbital fissure width and elevated tear film osmolality contribute to the cause of the dryness.4,8 Other studies have proposed that the dryness is due to impairment of the lacrimal gland from T cell dependent inflammation and increased evaporation of the tear film. Two metaplastic inflammatory changes in the temporal interpalpebral bulbar conjunctiva are observed in Graves’ disease patients with dry eye. Inflammatory factors such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 have been detected in the tear film of patients with dry eye, suggesting a relationship between the ocular surface inflammation and dry eye. Patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy frequently require ocular and systemic therapy. Our patient was on both topical and systemic therapy for the management of his condition, but still struggled with ocular discomfort and unstable vision.

Our patient presented with both keratoconus and ocular surface disease. Secondary to the complex nature of his presentation, mini-scleral lenses were selected to promote an increased tear reservoir while optimizing his vision. The Mini-Scleral Design™ lens by Blanchard Contact Lenses Inc, is a reverse geometry lens with an adjustable profile curve. The lens also has an aspheric front surface, a thinner profile, and high oxygen permeability to promote improved vision, comfort and corneal health. The fitting guide for the MSD lens is based on sagittal depth rather than on base curve with the goal of vaulting the cornea and the limbus; providing an adequate tear reservoir while creating a smooth refractive surface. The peripheral edge zone can also be adjusted for maximal scleral alignment. Available in a variety of sagittal depths and diameters of 15.8mm or 18.0mm, these lenses may be beneficial for patients with ocular surface disease and irregular corneas.

Although scleral lenses have not been indicated for treatment of ocular surface disease in patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy, theses lenses might allow some patients with irregular corneas to delay more aggressive intervention. A combination of dry eye therapy with these lenses allow for treatment and restoration of moisture from the liquid reservoir behind the lens to the cornea to prevent further damage.

Clear and comfortable vision may be achieved using mini-scleral or scleral gas permeable lenses. These lenses can contribute to the management of dry eye by allowing more tear reservoir from the vaulting of the lens and providing increased comfort due to the larger size.5–7,9–12 These lenses also provide refractive correction for the irregular and regular astigmatism. The tear film reservoir accumulated under the lens provides optical assistance for clearer vision. Irregular corneal changes from ocular surface disruption can often times make it more challenging to fit with regular soft contact lenses. The larger lens designs and a high Dk gas permeable material provide much success in the treatment of those with severe corneal disease and keratectasias.4–7 Larger diameter gas permeable contact lenses provide protection to the eye, acting as a barrier for insubstantial corneas against inflamed tissue of the lids.9–12 The size of these lenses also improves comfort as the lid margin interacts with the surface of the lens rather than the edge. The use of mini-scleral and scleral contact lenses has become a major indication for individuals who not only need a refractive correction but also suffer from irregular corneas and severe ocular surface disease.5–7,9–12Successful use of mini-scleral and scleral lens designs have been reported in the management of ocular surface disease.9–12 However, while the etiology of ocular surface dryness and the role of scleral lenses in patients with Graves’ are not clear, close monitoring of these patients is important to avoid potential complications. As with any lens fit, potential complications that may arise include corneal hypoxia, conjunctival and corneal staining, neovascularization, corneal infiltrates and microbial keratitis. These complications can be avoided with proper patient selection, fitting techniques, patient education, and with close observation. A few case reports have looked at the use of scleral lenses on an extended wear basis to protect the ocular surface.13 When prescribing these lenses as either daily wear or as for any ocular surface condition, careful consideration is needed to weigh the potential benefits and risks.

ConclusionMini-scleral and scleral lenses may be an option for patients with ocular surface damage and high amounts of astigmatism to optimize comfort and vision quickly. In these patients who have been diagnosed with severe ocular surface disease, scleral lenses may be considered as a therapeutic device to assist in rehabilitating the ocular surface and to determine their optimum vision potential. In this case, a mini-scleral lens design provided improvement in the patient's ocular surface, comfort and vision. However, further investigation is needed regarding the role of scleral lens designs in patients with Graves’ Ophthalmopathy.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.